Address: 235-241 Stuart Street

Built: 1881-1882

Architect: David Ross

Builder: Jesse Millington

Terraced houses were rare in Victorian New Zealand despite being common the United Kingdom, where most settlers were born and from where so many building styles were transplanted. Types of terraces there included not only working-class rows of plain design, but also the stylish townhouses of affluent city dwellers. There wasn’t much demand for such buildings in New Zealand, the colony being less urbanised, but of those that could be found many were in Dunedin, the most industrial centre. More than twenty terraces built between 1875 and 1915 survive in the city today.

One row in Upper Stuart Street still announces its original name to the world in large letters: Chapman’s Terrace. It was built between 1881 and 1882 as an investment property for Robert Chapman, and remained in family hands until 1910.

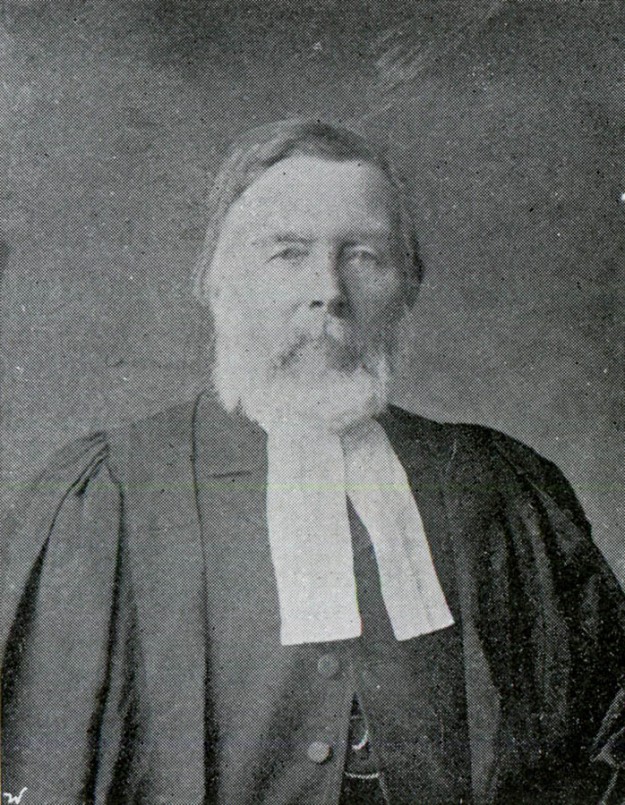

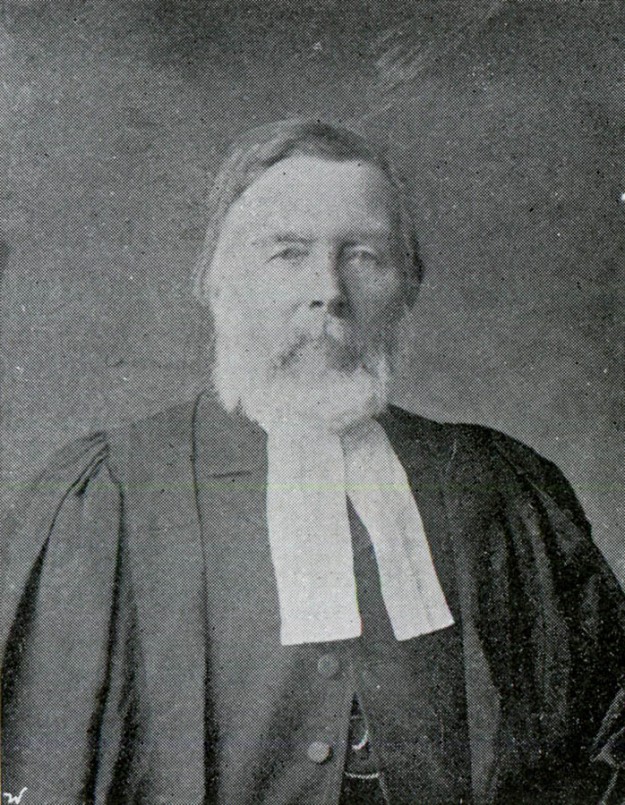

Chapman (1812-1898) was one Dunedin’s earliest colonial settlers. Born at Stonehaven, Aberdeenshire, he worked as a solicitor in Edinburgh before coming to Dunedin with his wife Christina on the Blundell in 1848. He served as Registrar of the Supreme Court and Clerk to the Provincial Council, but is probably most often recalled as the person who funded a memorial to Rev. Thomas Burns, built in the lower Octagon. Completed in 1892, it stood 19 metres tall and cost over £1,000 to build (as much as two ordinary houses). An immediate source of criticism and humour was that Chapman’s name was carved in the stonework in three places, at least as prominently as Burns’, but from what I can tell the donor was generally a quiet and unassuming sort of fellow and any lapse in modesty was uncharacteristic. The monument was demolished in 1948.

Robert Chapman (1812-1898)

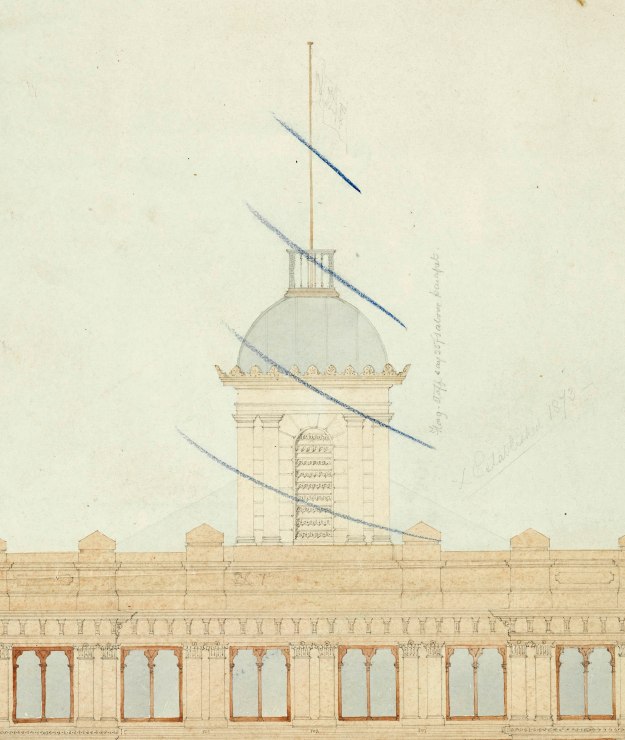

The memorial to Rev. Dr Thomas Burns, which stood in the Octagon from 1892 to 1948 (ref: Te Papa O.000998)

Robert’s son Charles, a lawyer who was Mayor of Dunedin at the time the monument was built, managed the tenancies of Chapman’s Terrace from its earliest years, and likely also had a hand in the building project. The architect was David Ross, who had earlier designed the terrace at 107-111 York Place, completed in 1877. Ross had been engaged by Chapman before, having designed Dunottar House and another villa residence for him.

The terrace was built in the Renaissance Revival style, and small but prominent porticos made striking features. The parapet originally had a balustrade, and its loss has affected the balance and proportion of the composition. Pairs of round-headed windows echo other designs by Ross, including Fernhill (John Jones’s residence) and the Warden’s Court at Lawrence.

Tenders for the project were called in September 1881 and the contractor selected was Jesse Millington, who at around the same time built Stafford Terrace at 62-86 Dundas Street (now known as the ‘Coronation Street houses’). The Stuart Street building was complete by the end of June 1882, when it was described in the Otago Daily Times:

The houses…are of a very superior class, both as regards design and convenience. The block comprises three houses, each of which contains 10 rooms, exclusive of bathroom, storeroom, pantry, &c. Two flats are above the streetline, and two below. All the rooms are fitted up with gasaliers and electric bells of an improved type. The buildings are an ornament to the upper portion of Stuart street, for they are nicely designed, and considerable expense has been devoted to external as well as internal finish.

Detail from a Burton Bros photograph showing the intersection of Stuart Street and Moray Place in the 1880s. Chapman’s Terrace is just up from Trinity Wesleyan Church. (ref: Hardwicke Knight, Otago Early Photographs, third series)

The steep site falls sharply away from the street, and though the building appears only two storeys high from the front, four levels can be seen from behind. The lower ones were built with bluestone walls, the upper ones in brick with cemented fronts. Each street entrance is almost like a little drawbridge, and there is quite a drop behind the iron railings.

The houses were first advertised as ‘suitable for professional men’ and their central location was one of their best selling points. When Thomas Miller left the upper house in 1885, an auction advertisement gave some idea of the furnishings inside:

Magnificent piano (in walnut, trichord, trussed legs, and every modern improvement by Moore, London), walnut suite (in crimson silk rep), large gilt-frame pier-glass, mahogany table and cover, tapestry window curtains, circular fender and fireirons, chess table, whatnot, Brussels carpets, hearthrug, cedar chiffonier, curtains, pole and rings, couch (in hair), dining-room table, cane chairs, sofa, linoleum, cutlery, napery, china, earthenware, B.M. dish covers, double and single iron bedsteads, spring mattress, cheval dressing-glass, 3 chests of drawers, washstands and ware dressing-tables, bedroom carpets, bed linen, blankets, quilts, kitchen table, chairs, sofa, floorcloth, kitchen and cooking utensils, culinary appliances, mangle, hall table and linoleum, door scrapers, mats, etc., etc., etc.

For periods each house was run as a boarding house or lodgings, with those who took rooms including labourers, carpenters, clerks, salesmen, music teachers, a share broker, a chemist, a photographer, a journalist, a draper’s assistant, a dressmaker, and many others.

From about 1890 to 1902 the upper house was run by Annie Korwin, and around the turn of the century it was known as Stanford House. Those who followed included Eliza and Honor Pye, James McKechnie, Elizabeth Scott, and Margaret and Enid Simmonds.

Helen Nantes was the first to occupy the middle house, and from 1885 to 1902 it was the residence of John Macdonald, a medical practitioner and lecturer at the Otago Medical School. Constance Alene Elvine Hall, known as Madame Elvino, occupied it from 1904 to 1910. Originally from Ireland, she variously advertised as a professor of phrenology, world-famed psychometrist, medical clairvoyant, metaphysical healer, business medium, hair colourist, palmist, psychic seer, and scientific character reader. She travelled widely around the country, giving consultations and running popular stalls at carnivals and bazaars. She married John C. Paterson, a sawmill manager, and he joined her in the terrace.

Advertisement from the Evening Star, 16 March 1906 p.5 (courtesy of Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand).

In 1908 Madame Elvino was charged with fortune telling, an offence under the Crimes Act, but acquitted on the defence of the celebrated barrister Alfred Hanlon, on the grounds that she had only given a ‘character reading’. She was convicted on another occasion in Christchurch in the 1920s. In a New Zealand Truth report titled ‘Face Cream and Psychic Phenomena for Frivolous Flappers’, Elvino was described as a ‘short, dark, plainly-dressed little woman, with a pair of twinkling eyes peering out from behind rimmed spectacles, she looks the last person on earth from whom one would expect any striking occult manifestations’.

William and Mary Ann Barry took the house after Madame Elvino, living there from about 1911 to 1932. During that time the First World War affected the residents of Chapman’s Terrace as it did all of Dunedin, and the Barrys’ only son was killed in action in France just a month before the armistice in 1918.

Early tenants of the lower house included the prominent music teacher Edward Towsey, and George Bell jr, managing director of the Evening Star newspaper. Those who lived in it for the longest spells were Alice Vivian, Eliza Pye, Mary Hutchinson, Mary Martin, and Robina McMaster.

Chapman’s Terrace in the early 1960s. Hardwicke Knight photo.

Chapman’s Terrace in the early 1960s. The fire escape dates from around the 1940s. The balustrade railing is still in place but balusters have been removed, giving something of a gap-toothed look. Hardwicke Knight photo.

In 1951, then known as ‘Castlereagh’, the lower house at 235 Stuart Street was purchased by the Dunedin Branch of the New Zealand Institute for the Blind. The refurbished rooms were opened in July 1952 and later the institute also acquired the middle house. After extensive alterations in 1960 (including the removal of partitions) the top floor contained a social room, braille room, and cloak rooms, while on the ground floor were a lounge, therapy room, cutting-out room, and the manager’s office. A new stair was less steep than the old one. The institute (later Royal New Zealand Foundation for the Blind) remained in the building until new purpose-built premises on the corner of Law Street and Hillside Road opened in 1975.

The terrace has been home to a legal practice since 1975, when Sim McElrea O’Donnell Borick & Thomas moved in. McCrimmon Law is now based here and in 2013 one of the building owners, Fiona McCrimmon, oversaw the extensive refurbishment of the terrace.

The balustrade was removed in the 1960s, but other original facade features remain happily intact, including pilasters with Corinthian capitals, square columns, quoins, and a dentil cornice. Some internal features that survived twentieth century alterations have also been preserved, including beautiful kauri floors, turned newel posts, ceiling roses and other plasterwork, and a few of the fireplace surrounds.

As someone who lived in the terrace for two years as student, I am delighted to see it so well looked after. I wonder if my old room was Madame Elvino’s…

The terrace as it appeared in 2012, immediately prior to renovations.

The terrace in 2015. The former Trinity Methodist Church on the corner is now the Fortune Theatre.

Rear view, showing the full height of the building, and the stone and brickwork (first painted over many years ago).

Basement detail

Facade detail

Lettering detail

Newspaper references:

Otago Daily Times, 1 September 1881, p.3 (call for tenders), 27 June 1882, p.4 (description), 29 August 1882, p.1 (to let), 7 October 1882, p.1 (board), 4 November 1885, p.4 (sale of furniture – Millar), 26 December 1885, p.4 (sale of furniture – Macleod), 4 April 1898, p.3 (Stanford House advertisement), 12 September 1898, p.3 (obituary for Robert Chapman), 18 July 1902 p.8 (Stanford House), 20 April 1951 p.6 (purchase by Institute for Blind), 22 July 1952 p.6 (official opening), 28 October 1960 p.5 (alterations), 8 April 1975 p.13 (new premises for Foundation for the Blind); Evening Star, 3 October 1891 p.2 (Burns Memorial – foundation stone), 30 April 1892 p.2 (Burns Memorial – handing over ceremony); Otago Witness, 17 October 1895 p.4 (Men of Note in Otago – Robert Chapman, Citizen and Solicitor), 15 September 1898 p.7 (obituary for Robert Chapman)

Other references:

Stone’s, Wise’s and telephone directories

Cyclopedia of New Zealand, vol.4 (Otago and Southland Provincial Districts), 1905, p.379

Plans for alterations, Salmond Anderson Architects records, Hocken Collections (MS-3821/2581)

Thanks to Fiona McCrimmon for showing me around the property