Built: 1912 (back portion 1908-1909)

Address: 21-33 Princes Street

Architects: Salmond & Vanes (James Louis Salmond)

Builders: Callender & McLeod (back portion C.W. Wilkinson)

In July 1935, Des Neilson attempted an 80-hour endurance record for stringed-instrument playing at the Green Parrot Tea and Dining Rooms, a basement café in Princes Street. The Evening Star reported:

Dunedin has stolen a march on America’s formidable list of ‘stunts,’ for never before has this one been attempted. At noon to-day, the youthful seeker of a Dominion record had played 44 of the intended 80 hours. Surrounded by a violin, a Spanish guitar, and a steel guitar (which accompanies his voice in yodelling numbers, just to break the monotony), Desmond reclined on a wicker settee, and told a reporter that his immediate wish was for a single feather bed. On a nearby table was an orange. His music has as yet made no difference to his diet, though his meals are varied by egg flips and beef tea. No, he is not tired, he asserts, but he certainly looks partly exhausted as his mitten-enclosed fingers quietly run across the strings of his instrument. Resort to massaging has been made, an attendant rubbing his back, stomach, and hands to the sound of vibrating strings. And when his audience is absent during long night hours he strolls up and down the floor to break the monotony. A signboard outside on the street and a periodic broadcast of his music by means of a microphone keep the public posted as to his progress.

A resident of King Edward Street, Des made regular concert appearances and radio broadcasts. At dances he led the Savonia Dance Band, formerly Dagg’s Band. Unfortunately, the record was not to be. Not long after speaking to the reporter he developed strong stomach pains and had to be assisted to a waiting car.

This is just one story of the buildings that have stood at 21-33 Princes Street since 1912. A long history precedes them. For centuries mana whenua sourced food, mahika kai, throughout the area. The site was at the northern foot of a large rocky promontory. To its south, at the mouth of Toitū stream, was the waka landing site of Ōtepoti.

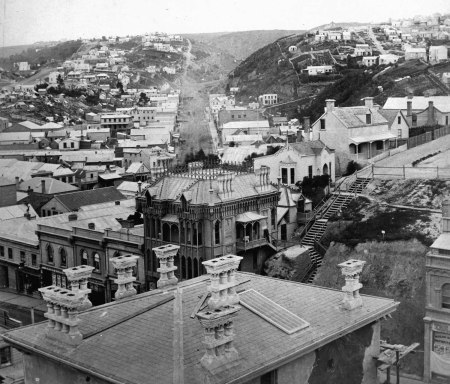

The colonial built history dates from after surveying in 1846, with the partial formation of Princes Street across the promontory, which became known as Church Hill and then Bell Hill. Around 1850, the steep and muddy street was traversed by its first wheeled vehicle: a cart pulled by a bullock named Bob. A cutting was put through in 1858, and a photograph taken two years later shows a re-formed Princes Street and a ragged-looking Octagon. Set back from and below from the street is a one-storey building with vertical weatherboards and shingle roof. Much original vegetation is gone, but the photo shows some native flaxes and scrub, as well as the denser growth of the Town Belt.

Demolition of the top of the Bell Hill began in late 1862. Earlier that year, Thomas Corbett built a three-storey wooden building up to the street line, dwarfing the old one behind it. Its three shops faced Princes Street, including Corbett’s own drapery, with another level below where the land sharply dropped away. Offices above were leased to the Provincial Engineer’s Office, and the whole took the name ‘Provincial Buildings’. All buildings on the site were destroyed in 1865, in one of the devastating block fires of the period.

The Octagon in 1860. The site of 21-33 Princes Street is partially occupied by the building at the bottom left. William Meluish photographer. Te Papa O.030506.

The Octagon in 1862. The old building remains, attached to Corbett’s new Provincial Buildings. William Meluish photographer. Te Papa O.030515. A good view of the front of the building, photographed by Daniel Mundy, can be seen at Toitū Otago Settlers Museum.

Corbett had a replacement built, possibly to the design of W.T. Winchester, in fire-resistant brick and stone. A portion became the Rodney Hotel, soon renamed the South Australian Hotel, with a hall in which one of New Zealand’s first roller skating rinks opened in 1866. The next year another big fire struck, and Corbett’s was the only building to survive on the eastern side of Princes Street, between the Octagon and Moray Place. The pub became the West Coast Hotel in 1879 and a skittle alley was attached. It lost its license in 1891. Others businesses on the site included the Comet Café, and signwriting firm N. Leves & Co., which in the 1880s had decorative figures painted on the facade.

In 1882, Mary Gill opened her Mrs Gill & Co. millinery and drapery business. In its early years it specialised in underclothing and millinery. It expanded and became known for women’s and children’s clothing more generally, and for fabrics, while Gill also taught dressmaking. The business was sold to David G. Ford in 1903, to James Ross & Co. (Otago Drapery Company) in 1907, and later the same year to Jeffery Moody. Moody had been apprenticed to the drapery trade in London in the early 1870s, and recalled being told: ‘You must, of course, dress in keeping with the position. While on duty in the shop you will have to wear a frock coat, a white bow tie, and “diamond” studs’.

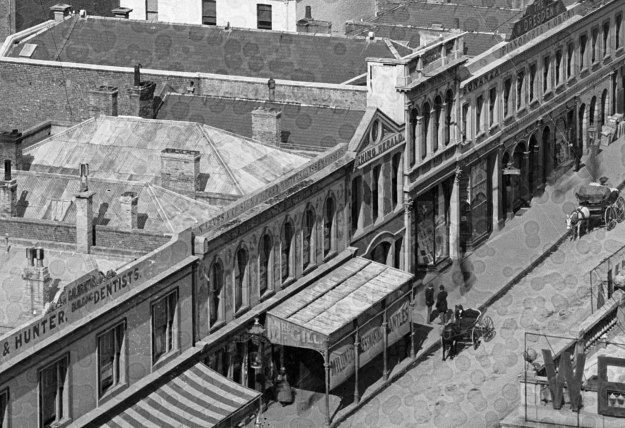

Detail from a Burton Brothers panorama, 1880. The first lamp belongs to the West Coast Hotel, and the second to the Comet Café. Between them is the shop of Leves & Scott (later N. Leves & Co.). The taller building is Charles Begg & Co. Te Papa C.012119.

A similar view from 1889. The verandah shows signage for Mrs Gill’s drapery. Leves & Co. have decorated the first floor facade. Burton Brothers photographers. Te Papa C.011961.

Baird’s Trust

Thomas Corbett died in 1898, and in 1900 his estate sold the property to Baird’s Trust. The trust had formed in 1895, when Borthwick Baird set aside a large part of his property for his nieces and nephews. Baird was born in Mid Calder, Scotland, in 1828. After a time in Australia he arrived in Otago in 1861. He was assistant to goldfields commissioner Vincent Pyke, gold receiver at Naseby, and clerk of the District Court of the Otago Goldfields. He became a wealthy investor and property owner, eventually purchasing Coronet Peak Station. His brother, Thomas Baird, was a storekeeper at Naseby. When Thomas died in 1897, Borthwick returned to his home village in Scotland, dying there in 1906.

New Buildings

The trust made a three-storey addition in brick, at the back of the property, in 1908. Salmond & Vanes designed it, and C.W. Wilkinson was the building contractor. The architects’ drawings show a handsome balustraded staircase and large rooms. Initially Jeffery Moody used this space, but his drapery was liquidated at the beginning of 1910 and the premises were taken on by Riedle & Scurr, land and financial agents and auctioneers. J.A.X. Riedle left the partnership in 1911, and the business changed its name to Scurr & Co.

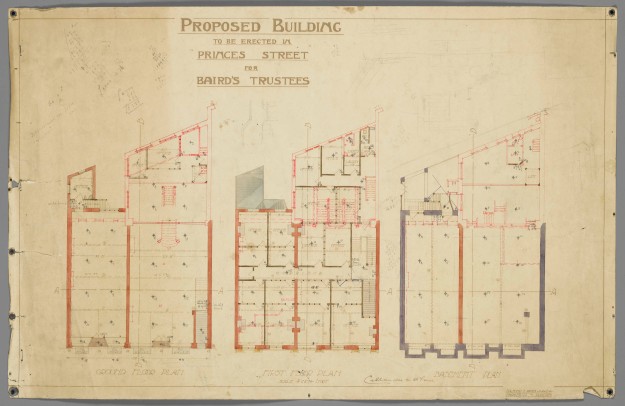

Architectural drawing showing floor plans for the rear portion of the current buildings, erected 1908-1909. Salmond & Vanes architects. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena MS-3821/2367.

Architectural drawing, foundation and sections, for the rear portion of the current buildings, erected 1908-1909. Salmond & Vanes architects. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena MS-3821/2367.

In January 1912 the front building was found to be in danger of collapsing into the street. In March, tenders were called for putting up a four-storey replacement. Callender & McLeod were the builders and Salmond & Vanes were again the architects. Louis Salmond’s diary records him consulting with the clients, drawing the plans, writing the specification, and supervising the work. He noted completion of the building on 20 December 1912, although it was not ready to be occupied until about April 1913.

Built on a concrete foundation, the building has a brick superstructure. The specification stated that none of the 1860s structure was to be retained, although bluestone from the basement level could be used for packing-in concrete. The facade is in an Edwardian style with Renaissance Revival and Queen Anne influence. Though exhibiting the trend toward simplified composition, the level of decoration still suggests a prestige building, with Oamaru stone facings, balustraded parapet, dentil cornice, and cartouches. The exposed rather than plastered brickwork was in ascendant fashion. So too were the casement type windows, increasingly preferred over hung sashes. The uninterrupted bays between the first and second floors give a sense of verticality where the overall proportions of the building might have made it appear squat.

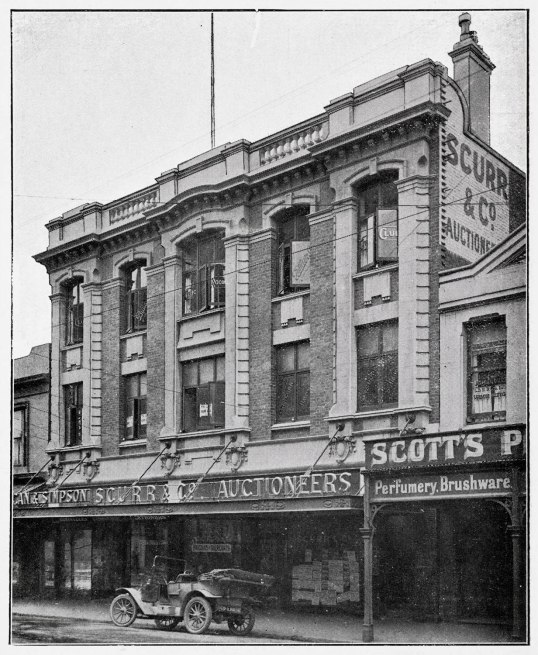

The building is sometimes referred to as Baird’s Building, and this name appears on the pediment in the original drawings. Once completed, however, it was known as Scurr’s Buildings. This was because the first major tenants were Scurr & Co., headed by Thomas Scurr, while upstairs were the rooms of lawyer Charles N. Scurr, the son of Thomas.

Front elevation drawing [1912]. Salmond & Vanes architects. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena MS-3821/2321.

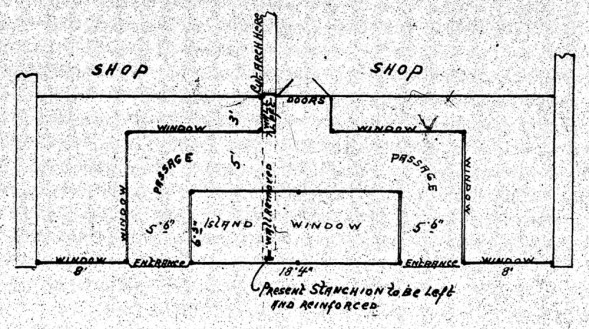

Floor plans [1912]. Salmond & Vanes architects. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena MS-3821/2321.

Sections and detail drawing [1912]. Salmond & Vanes architects. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena MS-3821/2321.

A view from 1916. Note the tall chimneys, later removed. Cropped from a photograph by R. Vere Scott. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena Box-287-001.

The Ground Floor

Scurr & Co. had a double front to the street but were not there long. They moved out in 1914, when the drapers and ready-to-wear specialists F. & R. Woods Ltd took their place. The name Scurr’s Buildings was still in use as late as 1924 but changed to Woods’ Buildings. The smaller shop at the Octagon end was taken by Duncan & Simpson, booksellers and stationers, from 1913 until 1923, when Woods expanded into the space. Alterations in 1927 included a new shopfront, finished in oak with a granite base, and with an island window display. The leadlight glass, in contrasting black and white, was reported to be the first of its kind in Dunedin. New interior features included fibrous plaster ceilings and X-ray shade lights. F. & R. Woods also expanded into the first floor of the Strand Building on the north side, where they opened a showroom. Another feature was a ladies’ restroom with settee, easy chairs, and a supply of writing materials.

At the end of 1933 the ground floor was once again divided to create two shops. Woods remained in the larger one until 1935. The National Electrical & Engineering Co. briefly occupied it before it became the Dunedin City Corporation Electrical Showroom in 1936. They shared this space with the Gas Department Showroom from 1942, and there was a workshop in the basement. Gas moved to another site in 1957, but Electrical remained until 1980, when it moved to the new Energy Centre in the Civic Centre.

The DCC Electricity Department Showroom c.1970. DCC Archives, Electricity Department Series Photos 14/1/6/2.

Hallensteins, which had its menswear shop across the street, opened a footwear outlet in 1981. This operated until 1987 when the shop became Vanity Wear, which lasted until about 1992. Last year, Card Merchant Dunedin opened here.

Chin Bin Foon opened the Central Fruit Co. in the smaller shop in 1934. By then he had already established the larger Sun Fruit business in Rattray Street. At Central Fruit he went into partnership with his cousin Chin Yew Kwong, who managed the shop. More of its history is told in the excellent two-volume publication The Fruits of Our Labours: Chinese Fruit Shops in New Zealand. Three generations of the Chin family worked here before the business was sold in the 1970s, and the shop continued to trade until 2001. The next year a Subway fast food outlet opened, and it is still there today.

A little tobacconists and newsagents faced the street from the late 1930s. It was originally in the space in front of the stairs, but was moved into a small front part of the shop space to the north. It was successively run by W.C. Ruffell, K.E. Bardwell, Frederick Grave, and P.B. Devereux, and finally became Esquire Bookshop, which closed around 1985.

The First Floor

On the first floor was the barrister and solicitor Charles Nunn Scurr. In 1907 he had joined in partnership Alfred Barclay, whose practice dated back to 1887. The rooms were sparsely furnished with linoleum flooring, typical of professional offices, and warmed with smouldering coal fires. Scurr was the Mayor of St Kilda when he died in the 1918 influenza epidemic, aged only 37. His practice was taken over by Alf Neill, as Scurr & Neill. Through various partnerships it eventually became Ross Dowling Marquet Griffin. The space was extensively refurbished in the 1960s and the firm remained until it moved across the road in 1986. Its total of 73 years on the site is yet to be beaten.

Many took rooms for short tenancies. In 1917 Fred George, metaphysician and clairvoyant, offered vibratory and magnetic massage and promised ‘evil habits cured’. First-floor tenants with longer tenancies included the tailor George Reilly (1910s-1930s), piano and elocution teacher Florence Clifford (1910s-1920s), dressmaker and costumier Margaret Gebbie (1920s-1940s), photographic retoucher Mary Ritchie (1920s-1950s), timber agent and architect J.D. Woods (1930-40s), and photographic artist Jessie F. Pollock (1930s). Pollock had been an employee of the well-known photography firm Wrigglesworth & Binns. Her services included tinting and enlargements, and in 1932 she advertised: ‘Bring your cherished photographs to Miss J. Pollock and have a choice Miniature made’.

In January 1928 a fire broke out in Reilly’s workroom. This was gutted and the office of Alf Neill was also fire damaged, with records destroyed. Other levels of the building suffered smoke and water damage.

John Kernohan (1891-1975), a watchmaker and jeweller, had rooms on the first floor from 1919 until his retirement in 1964. Born in Dunedin, Kernohan had begun his apprentice with W.J. Paterson at the age of 14. An officer in the Machine Gun Corps during World War I, he was wounded at the Battle of Messines. He became particularly known for his work with clocks, and remarked that very few watchmakers liked handling them because they often had to visit houses and other buildings. He trained between fifteen and twenty apprentices. Kernohan was timekeeper for brass and pipe band competitions and a life member of the Horological Institute. In 1961 he and his wife Elizabeth organised an exhibition in Queenstown, of antique clocks gathered from around the country. ‘JK Jewellers’ continued to operate in the building for about five years after Kernohan’s retirement, and were then another four years in Moray Place.

’13th National Salon’ exhibition by the Dunedin Photographic Society, 1964. From Camera Craft: The Official Journal of the Dunedin Photographic Society (June 1964, p.8).

The Second Floor

The Civic Club, a billiard hall, was first on the top floor in 1913. It was promoted as handsomely and comfortably furnished, with five Alcock No. 5 commercial tables. ‘Novelty has been aimed at, but not overdone, and an effect has been obtained which is at once soothing and cheerful’. The Civic remained until its last proprietor, Hugh Healey, died in 1955. The Otago Art Society and Dunedin Photographic Society took a joint occupancy later that year. They refurbished the space and held exhibitions in it. The central location suited them well, but access was poor, with two flights of stairs and no lift. By 1963 the Art Society had moved its annual exhibitions to Otago Museum and in 1965 it moved out altogether. The Photographic Society stayed on until 1967.

The accountants Thomson & Lang moved in around 1968, remaining until about 1982. This firm had been founded by Thomas Henry Thompson in 1900 and operated until about 2015. In its later years it claimed to the oldest private accountancy firm in the world.

The Western Building Society, a Whanganui-based co-operative, also moved into the second floor in 1968. A new lift and staircase were installed in the summer of 1969-1970, much improving the access. Large neon signs were put up in 1970 and 1971. One on the roof replaced the one which since 1965 had advertised Bell Radio & TV. It gave the society’s name, while another on the facade gave the building’s new name: Western House. The rooftop sign survived until the 2010s. Western moved out about 1979 and merged with Countrywide in 1982. By then the ownership of the building had changed. It was the last asset of Baird’s Trust, which wound up following the sale of the building in 1976.

Since at least 2015 the upper floors have been home to The Learning Place, a vocational training institute.

‘Ern Society’. The last remaining part of the Western Building Society signage in 2013. It has since been removed.

The Basement

The basement was often used by the businesses immediately above, although at times others used it. In 1929 Woods’ drapery sublet it for an ‘Italian Art Exhibition’ managed by Antonio Salutini and directed by Giovanni Stella. This was a commercial venture and included marble statuary, advertised to ‘gladden your home with radiance of beauty and taste’. It included works by Rossi, Cambi, and Spinelli. The Green Parrot café, the scene of Des’s exploits, opened in the basement in 1932 and boasted ‘business men and women specially catered for’. In 1935 the Regent Dining Rooms replaced it, but only lasted a few months before closing. The auction of chattels included fourteen square tea tables, high-backed chairs, split cane occasional chairs, a seagrass settee, heavy linoleum, Axminster sofa rugs, Axminster carpet runners, and large wooden partitions.

As for our banjoist Des, later in the 1930s he performed as the ‘Yodelling Hobo’ as part of the Rosette All-Star Variety Company. He served overseas during the Second World War and was invalided home. Soon after he was jailed for breaking and entering, and theft. He later worked as a carpenter, moulder, and boilerman, and he died at Tokoroa in 1985. Following his session at the Green Parrot another man made the proprietor an offer, ‘to make an attack on the existing record for protracted piano playing’!

Newspaper references:

Otago Daily Times 11 March 1862 p.5 (Corbett’s building); 7 August 1865 p.5 (Corbett’s, reference to Winchester & Clayton); 28 December 1866 p.6 (skating rink), 5 April 1867 p.4 (fire); 15 April 1913 p.4 (billiard hall); 6 November 1913 p.11 (‘A Question of Rating: Corporation v. Baird’); 14 July 1917 p.1 (Fred George); 26 February 1921 p.7 (Pollock); 2 March 1932 p.1 (Pollock); 28 April 1932 p.9 (Green Parrot opening); 9 August 1927 p.10 (description of alterations); 31 October 1929 p.17 (Italian Art Exhibition); 13 December 1929 p.13 (Italian Art Exhibition); 11 August 1936 p.11 (Electrical showroom cooking demonstrations); 14 February 1942 p.5 (shared electrical and gas showrooms); 3 January 1976 p.8 (Kernohan obituary); 13 August 1986 p.31 (Ross Dowling Marquet Griffin).

Evening Star 22 October 1908 p.2 (additions at Moody’s); 13 February 1909 p.4 (builders nearly finished); 27 March 1909 p.5 (conveniences); 7 May 1909 p.10 (new fur department); 15 April 1913 p.6 (billiard hall); 7 November 1917 p.3 (Kernohan, World War I); 30 January 1928 p.6 (fire); 28 July 1932 p.11 (Green Parrot advertisement); 19 July 1935 p.10 (Des Neilson at the Green Parrot); 20 July 1935 p.14 (Des Neilson record attempt); 10 August 1935 p.17 (Regent Dining Rooms); 14 May 1935 p.10 (National Electric); 30 July 1935 p.14 (pianist offer to the Green Parrot); 15 October 1935 p.12 (Regent Dining Rooms auction); 13 August 1936 p,12 (National Electric withdrawal from retail); 18 March 1961 p.3 (Kernohan exhibition).

The Press (Christchurch) 20 September 1949 p.6 (93rd birthday of Jeffery Moody); 10 November 1982 p.27 (Western merger with Countrywide).

Manawatu Standard 21 September 1938 p.2 (Rosette All-Star Variety Company).

Other sources:

Duncan, Ian N., ‘The stories of the lives and descendants of Borthwick Robert Baird and Thomas Baird’. Hocken Collections Misc-MS-2029.

Ledgerwood, Norman. The Heart of the City: The Story of Dunedin’s Octagon (Dunedin: Norman Ledgerwood, 2008) pp.8-9.

Prictor, W.J., Dunedin 1898 [map], J. Wilkie & Co., Dunedin, 1898.

Tod, Frank. Pubs Galore: History of Dunedin Hotels 1848-1984 (Dunedin: Historical Publications, [1984]).

‘Dunedin family firm sets world record’ in Chartered Accountants Journal vol. 87 issue 5 (June 2008) pp.14-17.

Architectural drawings, Salmond Anderson Architects records, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, MS-3821/2367 and MS-3821/2321.

Specification, Salmond Anderson Architects records, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, MS-3821/2367 and MS-3821/0295.

Diaries, Salmond Anderson Architects records, Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, MS-4111/011 and MS-4111/012.

Council of Fire and Accident Underwriters’ Associations of New Zealand, block plans, 1927

Stone’s Otago and Southland Directory

Wise’s New Zealand Post Office Directory

Telephone directories

Dunedin City Council permit records and deposited plans