Address: 18-20 Dowling Street

Built: 1882-1883

Architect: David Ross (1828-1908)

Builders: Meikle & Campbell

Burton Brothers photograph (Hocken Collections AG-295-036/003)

I’ll start with one of my favourites…

Hallenstein Brothers opened New Zealand’s first clothing factory in 1873 on a site off Custom House Square (the Exchange). Just ten years later they put up this fine pile, which company historians later described as their ‘quietly imposing headquarters’. Excavation work began in October 1882. To celebrate the opening of the building, a ball attended by 500-600 staff and friends was held a few doors down the street at the Garrison Hall on 23 July 1883. Contractors Meikle & Campbell received the final payment of their £8,500 bill in October.

The building is larger than it might first appear as its depth (67 metres) is four times greater than the street frontage. The top two floors originally housed the clothing factory, with a showroom and the company’s head office on the first floor, and a warehouse and leased-out premises on the ground floor. As many as 300 employees worked in the factory at one time and I like to imagine the busy traffic up and down the stairs, the activity of the (mostly female) workers on the factory floor, and the ‘pleasant hum of voices’ not overpowered by the rattling away of 80-odd sewing machines (most of them Singers). An ‘amusing stampede’ to the dining room, where free tea was served, took place daily at exactly 1pm when everyone had to leave the workroom, where windows were opened to ventilate the space. In 1900 the output of the factory was estimated at 3,000 garments a week.

Alice Woodward started at HB’s as a 14-year-old in 1914, earning 5 shillings a week making coats at a time when much of the sewing was still done by hand. She found it run strictly, with the front door shut at precisely 8am and latecomers having to wait outside for fifteen minutes before being let in. Alice stayed for 57 years, retiring as a machinist in 1971, at which time there were about 75 working in the sewing room.

A separate business, Michaelis, Hallenstein and Farquhar, had their offices and a warehouse in the lower part of the building from 1883 to 1957. Renamed Glendermid Ltd in 1918, they were leather merchants and established the large tannery at Sawyers Bay.

Inside the clothing factory (Hocken Collections AG-295-036/003)

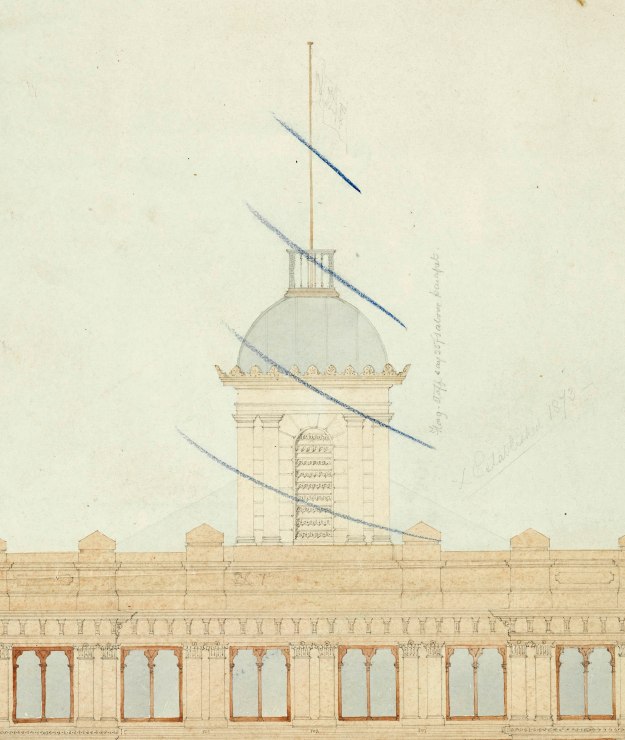

Architect David Ross was a Scotsman who worked in Dunedin from 1862 and the factory was one of his last projects here before he moved to Auckland. Ross designed some of Dunedin’s most familiar buildings, including the Congregational Church in Moray Place and the older part of the Otago Museum. Although he sits a little in the shadow of the famous Mr Lawson, he remains the only Dunedin architect to have become a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Ross had travelled extensively in Europe and the USA and his entrepreneurial client, Bendix Hallenstein, had looked at factory design and equipment in England. I wonder how much their observations influenced the Dunedin design, which was enlightened in terms of health and comfort in a decade when conditions in other local factories led to the infamous sweated labour scandal.

This is a renaissance revival building: ‘of the ordinary Italian street description’ according to an advance newspaper report. It draws strongly from the palazzo, which is seen in such features as the loggia-like arches at the ground floor and small windows on the upper floors. The bold cornices give horizontal emphasis. It’s strong and unfussy, but there’s also much richness in its detail. Some of its features recur in Ross’s work, including the pairs of round-headed windows and the banded rustication. The windows on the top floor of the facade repeat the treatment he used on the ground floor of the museum. The row-of-circles motif he frequently used elsewhere only appears on an alleyway gate.

The ground floor walls of the building are stone, with finely carved Port Chalmers breccia used for the facade and Leith Valley andesite for the other elevations. The upper floors are constructed in triple brick and plastered on the street front. The alleys on either side are among the most delightful in Dunedin and a large boiler survives at the back where the building abuts the stone of Bell Hill. Inside the factory chamber, which was originally ‘delicately adorned in tints of blue and white’, an innovative lantern-like roof structure with many windows and skylights keeps the space well lit.

The facade is little altered. The bridge over the alleyway is an early addition said to have been built to accommodate a board room, the ground floor doorways have been relocated more than once, and a few windows have been replaced unsympathetically. A pleasant but slightly busy paint scheme highlights some of the architectural details. It’s a bit of a shame that signage covers the old clothing factory name with its period lettering but this could be removed in the future.

In 1968 Ted McCoy and Gary Blackman identified the building as the best of Dunedin’s early warehouses. It was registered as a Catergory I Historic Place in 1988, the same year that Hallensteins’ head office left Dunedin. The building has been the home to Milford Galleries since 1989 and is now named ‘Milford House’. The Dowling Street Studios are also to be found here, while another tenant is the Christian Outreach Centre. The building was bought by Feldspar in 2010 and their involvement in heritage re-use projects such as Arrow House and Diesoline Espresso suggests it’s in good hands.

Newspaper references: Otago Daily Times, 19 September 1882 p.1 (call for tenders), 5 October 1882 p.4 (description – ‘shortly to be proceeded with’),12 October 1882 p.1 (contractors’ notice – excavation), 27 September 1883 p.3 (description following completion), 9 January 1900, p.2 (description); 4 May 1970, p.14 (changes), 21 December 1971, p.12 (Alice Woodward); Otago Witness, 28 July 1883 p.10 (ball to mark opening), 18 August 1883 p.8 (floor area); 7 June 1894, p.35 (description).

Other references: [Bathgate, John] (‘A Citizen’), An Illustrated Guide to Dunedin, and its Industries (Fergusson and Mitchell, 1883), p.102; Cyclopedia of New Zealand, vol. iv, Otago and Southland Provincial Districts (Christchurch: Cyclopedia Company, 1905), pp.306-7; Brasch, Charles and C.R. Nicolson: Hallensteins: The First Century 1873-1973 (Dunedin: Hallenstein Bros, 1972) pp.25-27; McCoy, E.J. and J.G. Blackman, Victorian City of New Zealand (Dunedin: McIndoe, 1968), plt 20; New Zealand Historic Places Trust registration no. 2159; Bendix Hallenstein letterbooks (Hocken AG-296/005); Hallenstein Brothers general ledger (Hocken AG-295-015/028).