Built: 1928

Address: 2 Manse Street

Architect: William Henry Dunning (1872-1933)

Builders: G. Lawrence & Sons

The building in July 1975, photographed by and reproduced courtesy of Ray Hargreaves. Hocken Collections S13-127b.

For decades, neon signs at Barton’s Corner brightened Dunedin’s night life and made the 1920s butchery buildings a city landmark. Little pink pigs ran along the verandah, green lambs leapt along the parapet, a suited pig doffed his top hat, and a large bullock capped it all off. The signs were especially popular with children, and many parents would slow their cars so the kids could enjoy the display.

The history of occupation on the site goes back to Māori settlement, although the level of the land was reduced by early Eurpean settlers. In 1851 James Macandrew, later Superintendent of Otago, built a store here. His single storey building was described nearly fifty years later as being ‘more attractive in appearance than any other in embryo Dunedin’. Macandrew was succeeded by James Paterson, who sold up in 1863.

Meanwhile, in 1853, Benjamin Dawson established Stafford House as a private boarding establishment on the site above in Stafford Street. Under John Sibbald it became Sibbald’s Private Hotel, which was given a license in April 1858. It was renamed the Provincial Hotel in 1859 and enlarged in 1861. It was probably in 1863 that the timber hotel buildings were extended down to the Manse Street corner, and at the end of the decade the ground floor portion became a shop (it was a grocer’s for some years). This extension was very narrow and a separate brick building took up most of the site facing Manse Street. The occupants of this second building included the Caxton Printing Company from 1889 to 1913.

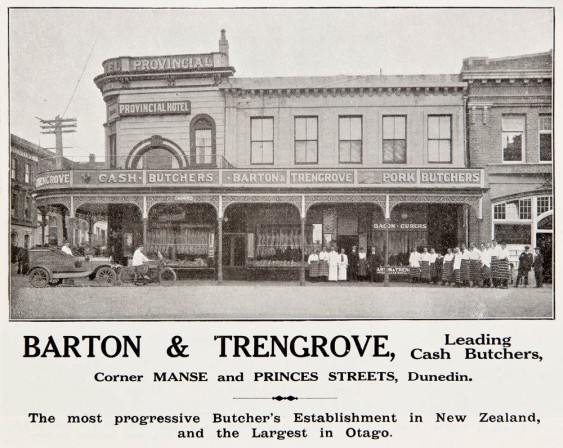

An advertisement showing the Barton & Trengrove butchery in 1918. It is housed in both the old Provincial Hotel additions (left) and the former Caxton Printing Co. building (right). Otago Witness, 16 October 1918 p.33. Hocken Collections S13-184.

Barton & Trengrove, butchers, opened on the site in 1913 and took both of the old buildings. George Barton was a young Australian who had been making his way to America when he saw an opportunity to go into business in Dunedin. His partner was John Trengrove, and both men were enterprising horse racing enthusiasts. Barton’s pacer Indianapolis rode to victory in the New Zealand Trotting Cup in three successive years and won over £10,000 in stakes. Trengrove sold his share in the butchery in 1924 and from 1928 it was known simply as Barton’s. In the same year a new building was erected, with demolition work started in January.

The building under construction. Otago Witness, 25 September 1928 p.44. Hocken Collections S13-127e.

Permit papers and deposited plans record the work as ‘additions and alterations’, as the new building incorporated an existing basement and some ground floor walls. Steel frame construction was used and the business was able to remain open on the site during the rebuilding. The upper storeys had steel-framed windows with fine decorative detail on the first floor bay windows. There was a light well within the building. The contractors were Lawrence & Sons and the architect was William Henry Dunning, who had previously worked in Tasmania before arriving in Dunedin in 1908. Dunning’s early designs here included the National Bank in Princes Street and Ross Home in North East Valley. A later work was the block of shops at the corner of Albany and George Streets, which has some similar decorative features to Barton’s Buildings, including Art Deco elements.

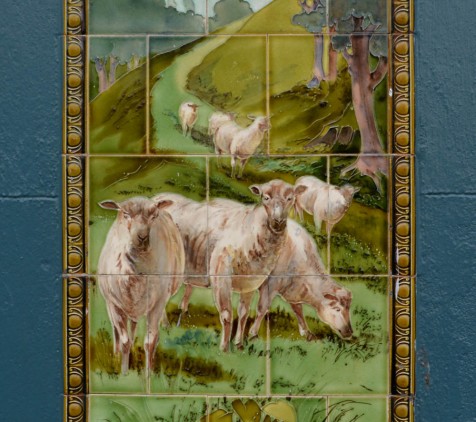

Dunning’s design was described in an Evening Star newspaper report as being in Renaissance style. This might seem a stretch, but the composition can be read as ‘stripped classical’, a style then in vogue and used on contemporaneous Dunedin buildings such as Queen’s Buildings and the Public Trust Office. There are also hints of an Egyptian Revival influence, including a winged cartouche at the top of the splayed corner. The facades were finished in white Atlas cement, lined with a block joint, and the shop fronts and internal staircase were finished with terrazzo. Crown Derby tiled panels depicting sheep and Highland steers were fixed to the ground floor facade facing Stafford Street.

Detail from one of the panels of Crown Derby tiles next to the Stafford Street entrance.

Barton’s flourished and a branch was established in Rattray Street in 1930, while George’s brother Douglas operated a butchery in the Octagon. In 1942, following the Japanese bombing of Darwin, an air raid shelter for up to 30 people was built in the basement of the Manse Street building. Quite a few of these were constructed in the central city and other businesses that built or planned shelters around the same time included the D.I.C., Penrose’s, and Woolworths.

George Barton junior eventually returned from service in the Air Force and took over the business together with his brother Reg in 1946. He later remembered that ‘After the war, all of the town was dull and dreary. We thought the place needed brightening up, so we decided to make a statement’. This was when the first of the neon signs were installed.

The signs were made by Claude Neon, who for more than 30 years owned them and leased them to Barton’s. A photograph taken in the early 1960s shows the running pigs, the lambs, and the cattle beast in place, with the name Barton’s displayed vertically down the splayed corner. In 1965 the name sign was replaced by a suited pig built by Trevor Hellyer, who was then a junior at Claude Neon. Hellyer also built the Fresh Freddie fish sign that was a familiar sight in St Andrew Street for 40 years. Another large sign reading ‘Barton’s’ was added to the Manse Street facade.

George Barton senior died in 1963 following a fall at the Burnside sale yards. He was 82. George junior and Reg ensured Barton’s remained a family business and took the butchery to its peak, when it employed over 200 staff, including 63 butchers. From 1967 special lamb cuts were exported overseas in a joint venture with PPCS, and major alterations and additions were carried out to allow the increase in production. Trade restrictions made this venture less successful than it might have been. The original shop fronts were taken out in 1969.

Reg Barton said the best way to beat the supermarkets was to offer a different product by going back to old-fashioned ways, and in 1978 the business announced it would revert to selling unpackaged rather than pre-packaged meat. By the end of the decade, however, the firm faced an estimated cost of $100,000 to bring its building up to Health Department requirements. The Manse Street shop closed for the last time on 29 January 1980. Other shops in Rattray Street and the Golden Centre remained open for a little longer (the Octagon shop had closed in 1966). The neon signs were removed in September 1980 and some were put into storage at the Dunedin Museum of Transport and Technology. The restored gentleman pig can now be seen at the Settlers Museum, and some of the running pigs are on display outside Miller Studios in Anzac Avenue.

From 1985 to 1995 Dick Smith Electronics were the ground floor tenants. G.S. McLauchlan & Co. bought the buildings in 1988 and redeveloped them to the plans of Mason & Wales, the work being complete by April 1989. The upper floors were converted to offices, the original central light well was built over, and more than 90 truck loads of rubble were removed from the site. The building was painted grey with details highlighted in white. The original ‘Barton’s Buildings’ lettering was removed and replaced with the new name, ‘Stafford House’ in black plastic lettering. This was a pity as the old lettering had a distinctive period style, and the material and font of its replacement is out of character.

The current name may reference the original Stafford House of the 1850s, although it’s not on the same site. To add confusion, the pink building on the opposite corner was also known as Stafford House for some years, as was the building that fronts the Golden Centre in George Street.

In the 1990s Stafford House got its current colour scheme and the Pet Warehouse has been the ground floor tenant since 2001. An association with animals continues, but in a very different way!

Update: Since I wrote this the building has undergone major refurbishment. Below is a view of the exterior taken in September 2014. The Barton’s name has returned and Dad’s photograph of the neon lights now decorates the lift!

Newspaper references:

Otago Witness, 17 December 1853 p.2 (Benjamin Dawson), 13 May 1854 p.1 (stable), 7 February 1854 p.4 (John Sibbald), 3 May 1856 p.2 (Sibbald), 14 April 1860 p.1 (Provincial Hotel).

Otago Daily Times, 16 November 1861 p.5 (hotel enlargement), 6 April 1863 p.2 (James Paterson), 7 September 1864 p.5 (transfer of licence), 20 June 1872 p.2 (grocery), 3 April 1899 p.6 (Macandrew’s store), 4 April 1963 pp.1 and 3 (obituary of George Johnson Barton), 29 June 1967 p.13 (exporting and expansion), 22 October 1970 p.13 (history of Barton’s), 1 March 1980 p.1 (closure), 4 September 1980 p.1 (neon signs), 17 September 1980 p.5 (signs), 7 April 1989 p.12 (redevelopment), 3 January 1995 p.25 (signs), 24 August 1996 p.1 (signs), 7 April 1989 p.12 (redevelopment), 25 October 2008 (Trevor Hellyer), 23 June 2012 p.36 (obituary of George Hobson Barton).

Evening Star, 27 December 1927 p.2 (description of building), 12 June 1928 p.2 (building progress).

Other references:

Stone’s Otago and Southland Directory

Wise’s New Zealand Post Office Directory

Block plans (1889, 1892, 1927)

Dunedin City Council permit records and deposited plans (with thanks to Glen Hazelton)