Built: 1880

Address: 132-140 George Street

Architect: Robert Forrest

Builder: John Brennan

There were eighty-nine licensed hotels in Dunedin in 1865, and that year the original Sussex Hotel was added to their number, making twelve pubs in George Street alone. A simple single-storey wooden structure, its first licensee was Henry Pelling, who was followed by Alfred Lawrence, Daniel Bannatyne, and then Thomas Oliver. Additions at the back designed by W.T. Winchester were built in 1877, and three years later Oliver had the front portion rebuilt at a cost of over £4,000, creating the three-storey brick building seen from the street today.

The architect was Robert Forrest (c.1832-1919), whose other designs included the Excelsior, St Kilda, Green Island, and Outram hotels. The facade was in the Renaissance Revival style, with massive pilasters running between the top two floors, and an unusual curved corner at the entrance to Blacket Lane. There were originally more mouldings than there are now, as well as an arched pediment and finials prominent on the parapet. The builder was John Brennan and the building was complete by June 1880.

The hotel contained a bar, two parlours, a sitting room, a large number of bedrooms, dining room, billiard room, and a skittle alley. There were also two shops, with dwelling rooms above them on the first floor, and on the top floor was the Sussex Hall. This had room for 200 people, and events held there in the 1880s included dinners, concerts, dances, workers’ meetings, election meetings, wrestling matches, and boxing classes.

The Sussex Hotel under construction in 1880. Ref: Te Papa C.012110. Cropped detail from Burton Bros photograph.

The hotel was said to have had an unusual patron in its early years. Margaret Paul, historian of the neighbouring A. & T. Inglis department store, tells the story of Antionio, a ‘mansized ape’ that belonged to eccentric store owner Sandy Inglis. The story goes that Antonio, often found dressed in an admiral’s uniform, was served drinks at the hotel. He was also allegedly involved in incidents that included his assault of a barman who had doctored his drink, an unsuccessful attempt to ride a horse (not his idea), and a scene at Port Chalmers when he threw lumps of coal at well-dressed locals returning home from church. Sadly, it is said he was shot after having a go at Sandy himself. Of course legend is typically more colourful than real events, but a newspaper of 1881 records that Inglis did a least own a ‘celebrated South African monkey “Antonio”’, and that he attracted the ‘wonder of an admiring multitude of small boys’ on at least one parade. Inglis also acquired a baboon, and both of the poor animals had been brought to Dunedin by Captain Labarde of the Pensee, and exhibited at the Benevolent Institution Carnival in 1880.

An advertisement from the Otago Daily Times, 28 June 1894. Thanks to Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

Licensees after Oliver (though he retained ownership of the building) were Thomas McGuire, Michael Fagan, John Toomey, and Joseph Scott. Oliver returned in 1894 and improvements made at that time included a new ‘American Bowling Saloon’ and a rifle gallery. The license transferred to Jessie Guinness in 1896, and then after her marriage to her new husband, John Green. The hall was used as band and social rooms, and for some of Dunedin’s earlier screenings of motion picture films. An unusual event in 1902 included J.D. Rowley’s Waxworks of Celebrities, a cyclorama (panoramic images on the inside of a cylindrical platform), a Punch and Judy show, a mechanical organ, and a penny-in-the slot machine ‘which purports to reveal the future and inform the inquirer what is the nature of the matrimonial alliance he or she is destined to contract’.

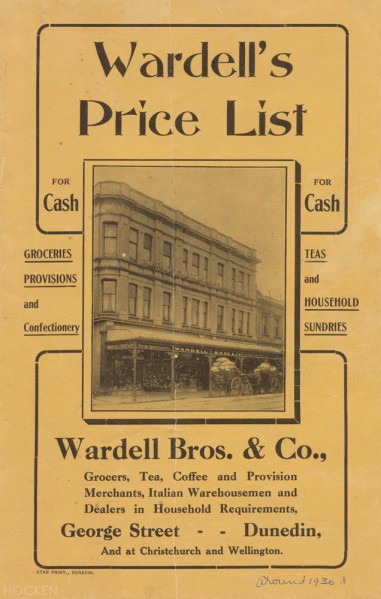

In 1902 a vote was passed reducing the number of hotel licenses, and the following year the Sussex Hotel’s days as a pub came to an end, although it continued as a private hotel for a few more years. Its next phase was as Wardell’s Building. The grocers Wardell Bros & Co. opened a grocery store on the site in 1907, having first established outlets in Dunedin and Christchurch in 1889, and a branch in Wellington in 1893. For many years Wardells was the largest store of its type in Dunedin, known for its free home delivery service, and for stocking products not available elsewhere, such as specialty cheeses.

One of the most notorious New Zealand riots centred on Wardells during the Great Depression. On 9 January 1932, hundreds of unemployed workers protested in George Street demanding food relief, and attempted to break into the store. A window was broken but the crowd was unsuccessful in its attempts to get past police.

In 1935 the Dunedin business became a separate entity registered as Wardells (Dunedin) Ltd, which leased premises from a separate Wardell family company. In 1958 the store was converted to a self-service ‘foodmarket’ and outlets later opened in South Dunedin and Kaikorai Valley. Free deliveries ended in 1972 and in 1974 the firm was sold to Wilson Neill Ltd, which closed the George Street store in June 1979.

From its earliest years the Sussex Hall was used for boxing classes, and for followers of the health and strength training movement known as Physical Culture. The Sandow School of Physical Culture used the premises from 1901, and in 1904 was succeeded by the Otago School of School of Physical Culture, continued by J.P. Northey from 1906 to about 1953. Northey is remembered today as a pioneer of physical education in New Zealand. In the illustration below words can be seen emblazoned on the walls next to the stage, reading ‘Breathe more air and have richer blood’, and ‘Deep breathing is internal exercise’.

Northey’s School of Physical Culture in the Sussex Hall. Ref: Alexander Turnbull Library PAColl-0318-01.

Dance studios operated in the building from the 1950s through to the 1980s. Shona Dunlop-MacTavish ran one of the first modern dance studios in New Zealand, and other instructors and groups included Laura Bain, Lily Stevens, Serge Bousloff (formerly of the Borovansky Ballet), Helen Wilson, Robinson School of Ballroom Dancing, the Ballet School, Southern Cross Scottish Country Dancing Club, Otago Dance Centre (Glenys Kindley and Alex Gilchrist), and Meenan’s School of Ballet. The New Edinburgh Folk Club also had its first rooms in the building.

There have been many physical and practical changes to the building. A bullnose verandah was added in the 1890s and replaced by a suspended one in 1933. Major additions at the back were made in 1908 (Luttrell Bros architects) and 1936 (Miller & White), replacing earlier structures. An air raid shelter was built after the Japanese bombings of Pearl Harbor and Darwin in 1942, and it was one of many constructed in the central city at the time. The finials and pediment were removed prior to 1930 and the front of the building was replastered in utilitarian fashion in 1956, with the loss of many original mouldings. Window canopies date from the 1990s. Blacket Lane remains one of Dunedin’s most fascinating and beautifully layered urban alleys, with high walls of mixed stone and brickwork.

From 1979 a succession of appliance stores operated from the retail space formerly occupied by Wardells. These were Kelvinator House, Wilson Neil Appliances, and Noel Leeming. In 1995 the Champions of Otago sports bar opened at the rear of the ground floor, and in 2006 this was replaced by Fever Club, a 1970s disco-themed bar. Wild South and Specsavers now occupy the ground floor shops, while businesses upstairs include Starlight , Chinese Christian Books & Gifts, Travel Partners, and Alan Dove Photography. The use of the building continues to be diverse, as it has been since 1880.

Newspaper references:

Otago Daily Times, 21 June 1865, p.4 (establishment of Sussex Hotel), 16 November 1877 p.3 (additions designed by Winchester), 27 February 1880 p.3 (description of building), 21 June 1880 p.2 (monkey and baboon), 8 July 1880 p.3 (dinner), 27 August 1880 p.1 (concert), 4 September 1880 supp. p.1 (railway employees), 7 January 1881 p.2 (butchers), 21 September 1881 p.2 (Antonio), 6 July 1882 p.1 (boxing classes), 8 August 1882 p.3 (baboon), 27 April 1901 p.1 (physical culture), 11 July 1908 p.11 (physical culture), 17 September 1995 p.B12 (Champions of Otago opens), 17 November 2006 p.24 (Fever Club opens).

Other references:

Stone’s, Wise’s, and telephone directories

Dunedin City Council permit records (with thanks to Glen Hazleton)

Council of Fire and Accident Underwriters’ Associations of New Zealand. Block plans, 1927.

Baré, Robert. City of Dunedin Block Plans Dunedin: Caxton Steam Printing Company, [1889].

Calvert, Samuel (engraver after Cook, Albert C.). Dunedin, published as a supplement to the Illustrated New Zealand Herald, July 1875.

Dougherty, Ian. High Street Shopping and High Country Farming: A History of Wardell and Anderson Families in Otago. (Dunedin: Mahana Trust, 2009).

Jones, F. Oliver. Structural Plans of the City of Dunedin NZ, ‘Ignis et Aqua’ series, [1892].

Paul, Margaret. Calico Characters and their Clientele: A History of A & T Inglis Department Store, Dunedin, 1863-1955. Nelson: M. Paul, 1998.

Wardells (Dunedin) Ltd price lists, Hocken Collections MS-4076/001.