Rebuilt: 1934-1935

Address: 362 Moray Place

Architect: Cecil Gardner Dunning

Builders: Love Construction Co.

One of Dunedin’s more jazzy and original expressions of the Art Deco style has been home to the Otago Pioneer Women’s Memorial Association for 75 years.

In the nineteenth century its Moray Place site was part of a large coal and firewood yard. In 1909 a single-storey structure was built for the consulting engineer William James as an office, together with a shop he rented out. An extension followed in 1913.

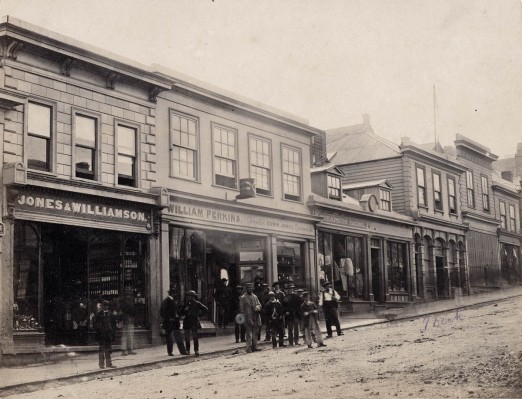

The site as it appeared in 1874, with Stuart Street in the foreground. Detail from Burton Bros panorama. Te Papa O.025698.

Elevation and section plans of the original building, erected for William James in 1909.

The building gained an additional storey and its distinctive style in 1934 and 1935, through work carried out for new owners S.R. Burns & Co. by the Love Construction Co. Stanley Burns was a decorated returned soldier, who served in France in the First World War. He ran a tailoring business in Dunedin before setting up a company dealing in shares and the promotion of subsidiary companies with diverse interests in property, printing, caravans and camping equipment, cosmetics, and other areas.

The architect for the work, Cecil Gardner Dunning, was the South-African-born son and former practice partner of another local architect, William Henry Dunning. The younger Dunning’s other Dunedin designs include the former customhouse (now Harbourside Grill) and numerous private residences.

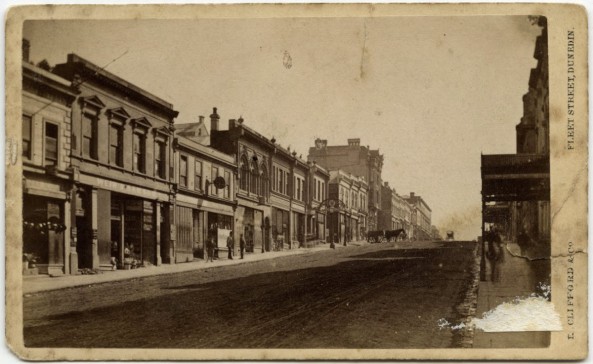

The facade as it appeared c.1935.

Bold and contrasting colours originally emphasised the angular design of the facade, likely including a warm red like the one recently revealed on the former Victoria Insurance Building in Crawford Street. The interior continued the theme, with its modern fittings, bevelled glass doors, and fashionable terrazzo flooring in the foyer and on the stairs.

The top floor was fitted out as a beauty salon for the subsidiary Roxana Ltd, ‘in accordance with modern trend and tastefully furnished to provide the maximum comfort to clients’. Much of this fit-out remains. Decorative elements included wood panelling in Pacific maple and Australian walnut ply, carnival glass windows, and black Vitrolite (an opaque pigmented glass) at the cosmetic counter and pay desk.

Sandford Sinclaire, a graduate of the Wilfred Academy of New York, managed the skincare and make-up side of the business. From a six by four foot cubicle, described as his cosmetical laboratory, came Roxana Beauty Preparations, with their ‘special exotic properties anticipated to appeal to women of fashion throughout New Zealand’. Equipment included what promoters claimed to be the country’s first Dermascope complexion analysis machine. The ‘coiffure section’ under the direction of Miss MacDonald, previously of Melbourne and Sydney, boasted the latest in hair-waving machines.

An advertising feature in the Otago Daily Times gave an evocative description:

‘The Roxana Salon, recently opened in Burns’ Buildings, Moray place, has an air of up-to-date efficiency about it. Its lounge, approached by marble stairs and furnished with a brown patterned carpet, tawny hangings, and comfortable couches, has modern lights and modern furniture, particularly in its chromium and black glass table, and its reception desk with its black glass background, chromium fittings, and blazoned glass walls. Beyond are the cubicles, ivory walled and grey floored, with a glitter of chromium and glass about them, and an atmosphere of cleanliness and brightness. All the implements are kept in perpetually sterile cupboards, and tidiness is a watchword of the place. The salon has its own dispensary and boasts that it uses the best obtainable ingredients for its cosmetics. Features of the salon are its telephone in every cubicle; its personal records of the work done for every customer; its dermascope – said to be the only one in New Zealand, used to diagnose skin diseases and analyse the skin; its special hair-dressing, realistic waving, and washing apparatuses; its unobtrusive ivory-coloured heaters; and its home service. This last is perhaps most important of all, for it includes the free use of cars to take clients to the salon, and the treatment of clients in their own homes – before dances, weddings, theatres, and so on – or in hotels. The salon is in capable hands. Mr S.B. Sinclaire, cosmetician and dermatologist, is a graduate of the Wilfred Academy of New York and a specialist in colour harmony; Mrs Farrell, who assists him recently worked for Coty in Paris; and Miss R.M. McDonald, who is in charge of the coiffure section, has had extensive experience in Sydney and Melbourne and owns a Mayer Diploma as a qualified expert in permanent waving.’

Sinclaire was dismissed for incompetence after less than a year and the salon closed in August 1937. Cosmetics continued to be produced for a short period under a new Eudora brand. By 1941 Burns’s small empire was crumbling amid financial losses and fraud (he was imprisoned in 1943) and his building was sold to the newly-formed Otago Pioneer Women’s Memorial Association.

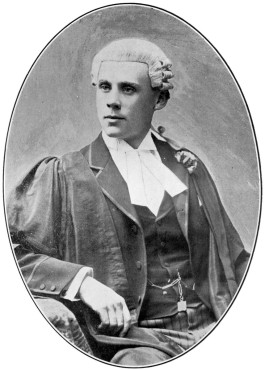

Dr Emily Siedeberg-McKinnon, the founding president of the association, was New Zealand’s first woman medical graduate. She worked as a general practitioner in Dunedin from 1897, and among her many other roles was Medical Superintendent of St Helen’s Maternity Hospital. Her house in York Place features in a previous post on this blog.

In 1928 she visited the Women’s Building in Vancouver, Canada. Over one hundred women’s groups used this new and central facility, which inspired her to promote something similar for Dunedin. She did not find an opportunity until 1936, when the recently-elected Labour Government announced extensive plans and regional funding for the upcoming New Zealand Centennial celebrations. Provincial committees were established, and on 31 July 1936 Siedeberg-McKinnon chaired a meeting to explore the idea of a memorial to Otago’s pioneer women. Proposals included a memorial arch, the cleaning up of slum areas, and a quaintly-described ‘home for gentlewomen of slender means’, but the delegates representing thirty-nine women’s organisations agreed they should pursue the idea of a women’s community building. The Otago Women’s Centennial Council was formed to further the project.

Dr Emily Siedeberg-McKinnon (1873-1968)

The new group had the support of Dunedin’s Labour mayor, Edwin Cox, and in February 1938 its proposal gained formal approval from the Provincial Centennial Council. It agreed that a women’s building should be one two major memorials for Otago, with the other being a cancer block at the public hospital.

In the following months Siedeberg-McKinnon outlined a proposal for a two-storey building with five committee rooms, a conference and concert room, a public lounge, two smaller lounges, a kitchen, and caretaker’s quarters. It would be available to both women and men and be similar in size to the Order of St John building in York Place. An obelisk dedicated to Otago pioneer women might be placed outside the entrance. The cost was estimated at between £7,500 and £10,000.

Cox was defeated at the local body elections in May, and while fundraising plans progressed, opposition to the scheme was finding traction. Earlier opposition had included some saying that women had no business wanting to go to meetings, and that their place was the home and the care of children. Sexism was a constant obstacle, and so were competing interests for the available funding. In September the new committee of the Provincial Centennial Council rescinded the original decision in favour of other schemes, cutting off access to the expected government subsidy. Siedeberg-McKinnon pointed to political and class bias, and to businessmen who favoured putting more money towards the national exhibition in Wellington, furthering their own commercial interests.

Perspective drawing of proposed community building on the Garrison Hall site, between Dowling and Burlington Streets. H. McDowell Smith architect.

Siedeberg-McKinnon encouraged supporters not to ‘crumple up at the first set back’ and plans continued to be developed for a general Memorial Community Building on the Garrison Hall site, between Dowling and Burlington street. The Provincial Committee again rejected the plans, and by this stage it was obvious it would not support funding any women’s or community building.

Dispirited, Siedeberg-McKinnon had a vivid dream in which she climbed from a walled enclosure, found her way through marshy ground, and looked up to see a large unfinished building with scaffolding around it. Encouraged, she found support to renew her efforts and led the formation of the Otago Pioneer Women’s Memorial Association at an ‘indignation meeting’ on 14 March 1939. The new name was necessary as legislation reserved the word ‘centennial’ for official projects and the group had been threatened with legal action.

Successful fundraising and a mortgage allowed the purchase of the Burns & Co. building and the refurbished property opened on 23 February 1942. Intended as temporary accommodation, the association remains there three-quarters of a century later.

The largest room was the hall. Other spaces included a boardroom and a lounge. A small chapel on the first floor named the Shrine of Remembrance was dedicated on Otago Anniversary Day 1946. Designed by architect Frank Sturmer, it was furnished with an oak chair made by Dunedin’s first cabinetmaker, John Hill, and a new oak refectory table by local Swedish-born cabinetmaker Alfred Gustafson.

Robert Fraser designed a memorial stained-glass window set within three gothic arches, but due to his failing health the work was taken on and executed by John Brock. The central panel shows Christ walking on water and his disciples in a rowing boat. The left-hand panel illustrates a migrant family departing Britain, and the right-hand panel depicts arrival in Otago. The arrival panel includes mother and daughter figures, the ship Philip Laing, a whare, and native flora including ferns and cabbage trees. The shrine was later decommissioned and the window was moved to the foyer. The inscription beneath the window reads:

This window commemorates the safe arrival in Otago of all those Pioneer Women who braved the dangers of the long sea voyage to assist in the settlement of the Province of Otago and is a tribute to their sterling qualities of character, their foresight, their self sacrifice and their powers of endurance through many hardships. A recognition by those who have reaped the benefit, spiritual or material.

The hall and rooms were made available to a wide range of community groups, and not exclusively women’s organisations. Those using the building in the 1940s and 50s included the Dunedin Kindergarten Association, Lancashire and Yorkshire Society, Rialto Bridge Club, Dunedin Burns Club, Federation of University Women, Practical Psychology Club, Sutcliffe School of Radiant Living, Musicians’ Union, Radio DX League, Otago Women’s Hockey Association, Registered Nurses’ Association, and many more. In 1960 over fifty organisations were using the hall and rooms. The Dunedin Spiritualist Church met in the building for nearly 50 years, from 1945 to 1994.

In 1958, the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Association purchased a new property in York Place and again entered a period of active fundraising. It appeared to be close to realising Siedeberg-McKinnon’s vision for a purpose-built building, but again fell short of its ambitious target. Instead, the unique venue they had developed was maintained and continues to provide a valuable community asset today.

With this post I mark five years of blogging on this website. Thanks all for reading.

Newspaper references:

Otago Daily Times, 17 September 1935 p.17 (Roxana advertising feature), 2 April 1936 p.16 (dismissal of Sinclaire), 8 March 1937 p.27 (outline of aims), 3 August 1937 (community building proposed), 9 February 1938 p.6 (approval by Provincial Centennial Council), 4 October 1938 p.5 (attitude of committee opposed), 15 March 1939 p.10 (OPWMA formed), 24 April 1940 p.6 (annual meeting, history), 30 April 1941 p9 (need for headquarters), 23 October 1941 p.9 (building purchased), 24 February 1942 pp.3-6 (opening), 28 May 1942 p.6 (‘aims partly realised’), 25 March 1946 p.6 (memorial window), 30 May 1960 pp.4 and 10 (fundraising), 6 June 1960 pp.4 and 14 (usage); Evening Star 18 October 1938 p.1 (description of proposed building), 25 October 1938 p.7 (illustration of proposed building); 30 October 1958 (‘new building nearer realisation’), 14 May 1960 p.2 (fundraising), 24 May 1960 p.2 (fundraising); Weekly News (Auckland), 29 October 1941 p.14 (‘Headquarters as Pioneer Memorial’); The Press (Christchurch), 2 April 1936 p.11 (Sinclaire, wrongful dismissal case), 16 September 1943 p.6 (charges of fraud against Burns), 30 November 1943 p.7 (sentencing of Burns).

Other references:

Stone’s Otago and Southland Directory, various editions 1884-1954.

Baré, Robert, City of Dunedin Block Plans Dunedin: Caxton Steam Printing Company, [1889].

Jones, F. Oliver, Structural Plans of the City of Dunedin NZ, ‘Ignis et Aqua’ series, [1892].

Dunedin City Council permit records and deposited plans (with thanks to Chris Scott, Archivist)

Booking diaries from Otago Pioneer Women’s Memorial Association Inc. records, Hocken Collections MS-3156.

Newspaper clippings from Dr Emily Hancock Siedeberg-Mckinnon papers, Hocken Collections MS-0665/046 and 047.

McKinnon, Emily H. and Irene L. Starr. Otago Pioneer Women’s Memorial. (Dunedin: Otago Daily Times, 1959).

‘Eudora Limited, formerly Roxana Limited’. Defunct Company and Incorporated Society files, Archives New Zealand Regional Office, R43267.

‘Eudora Limited [Previously Roxana Limited] – Director’s Minute Book’. Archives New Zealand Dunedin Regional Office, R9071585.

‘S.R. Burns & Company Limited’. Defunct Company and Incorporated Society files, Archives New Zealand Regional Office, R43322.