Built: 1951-1954

Address: 90 Anzac Avenue

Architect: L.W.S. Lowther (1901-1970)

Builders: Love Construction Co.

The 1950s Streamline Moderne building that is home to the Hocken Collections was originally built as a dairy factory and offices. The Dunedin-based Co-operative Dairy Co. of Otago produced Huia brand butter and cheese for 75 years, and from this site for over 40. The company disappeared in the dairy mergers of the late 1990s, and their premises became the University of Otago’s new Hocken Library in 1998.

Outwardly, the building perhaps looks older than its years, although it was internally and practically up-to-date when new. It is a late example of a style of architecture introduced to Dunedin in the mid-1930s. Plans were ready in 1947, but there were numerous delays in securing permits and consents, followed by a long construction period of three years. The factory finally opened in 1954.

I’m getting ahead of myself though. First some earlier history of the dairy company…

Dunedin has a long a long association with the dairy industry. New Zealand’s first co-operative dairy factory opened on the Otago Peninsula in 1871, when the eight shareholders of John Matheson & Co. established the Peninsula Cheese Factory at Matheson’s Springfield property. The development of infrastructure and technology saw rapid growth in the industry from the 1880s, when further factories were built around the country. Improved transport networks, refrigeration in both factories and transportation, cream separators, new testing methods, and selective breeding all contributed to the rapid growth of an export industry in the decades that followed. Combined exports of butter and cheese grew from 5,000 tonnes in 1881, to 300,000 tonnes in 1901.

The Co-operative Dairy Co. of Otago formed in Dunedin in 1922. At that time, 564 dairy companies operated around the country, 88% of them co-operatives within a highly regulated industry. The new company claimed it was owned entirely by those who supplied cream, with ‘absolutely no dry shareholders’. 284 individuals operating home separators took 68% of the initial share allocation, while eight small Otago factories (Momona, Mosgiel, Milton, Goodwood, Waikouaiti, Merton, Omimi, and Maungatua) took the remaining 32%. The new company purchased the business of the Dunedin Dairy Co., taking over their newly-built premises opposite the railway station in June 1923. In doing so, it acquired the Huia brand, under which Dunedin Dairy had marketed butter since 1920. By the 1927/28 season the new co-op produced 800 tonnes of butter, the second largest output by a South Island factory.

The original building served the company for thirty years, but by the 1940s it was cramped and behind the standard demanded by regulators. The company bought out the butter business of the Taieri & Peninsula Milk Supply Co. in 1942, taking on its Oamaru factory, but it still sought to expand its Dunedin operation on a larger and more accessible site.

An area of reclaimed Otago Harbour Board land included a vacant and appealing site near the railway line on the east side of Anzac Avenue. The avenue had been built in 1925, in time to link the railway station with the New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition at the newly reclaimed Lake Logan. The idea of such a road been put forward by Harbour Board member John Loudon as early as 1922, before the exhibition was formally proposed. The development or reclamation of the lake had been anticipated for some years, and a new road would also improve connection with West Harbour. It was the exhibition, however, that brought the impetus needed to make what was then referred to as the ‘highway’ a reality. Exhibition architect Edmund Anscombe played a central role in the planning, proposing parks, reserves, and housing for the area to the east of the avenue, but it remained largely undeveloped through the depression years and up to the war.

A late 1920s photograph shows young trees lining the avenue, but by 1933 some had died and others were stunted. Most of the present elms were planted between 1934 and 1938, by school pupils participating in Arbour Day activities.

Detail from c.1902, from ‘Dunedin from Logans Point’ by Muir & Moodie. The future site of the co-op building is under water, next to the shoreline at the far left centre of the image. Ref: Te Papa PA.000184.

Anzac Avenue as it appeared about 1928, meeting Union Street and the southern edge of Logan Park. The future factory site is the furthest of the vacant land on the left. Ref: ‘Dunedin, New Zealand no. 872’, Alexander Turnbull Library Pan-0017-F.

An aerial view from April 1947, showing the vacant site at the centre of the image. Ref: Whites Aviation Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library WA-06920-F (cropped detail).

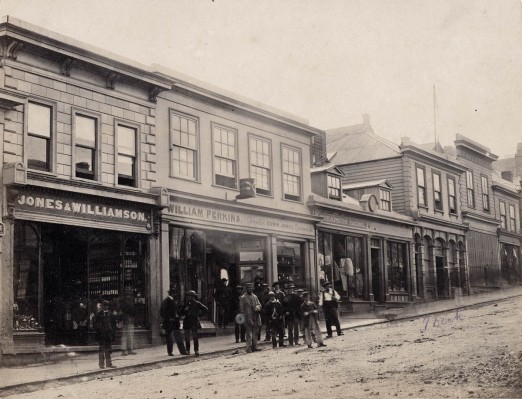

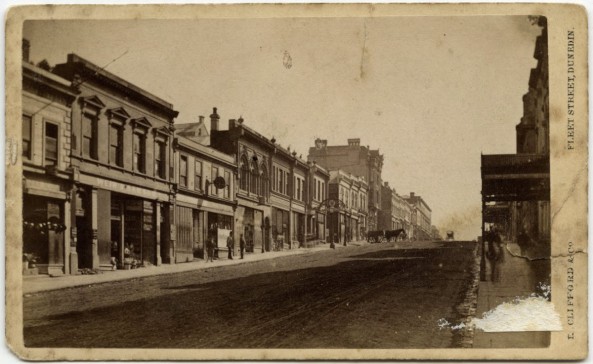

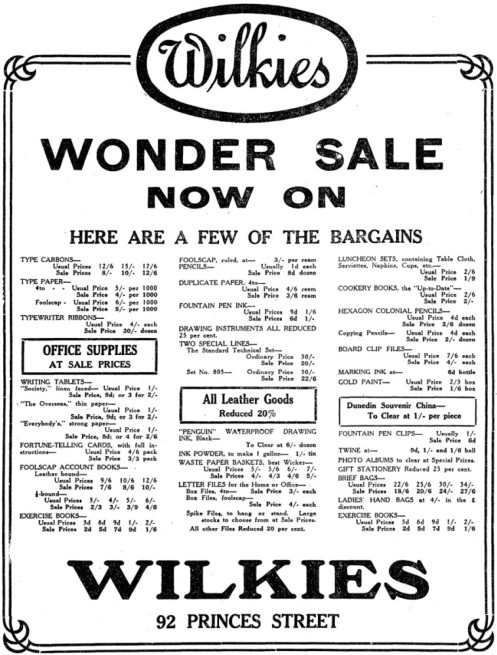

The new Dunedin North Intermediate School opened at the corner of Albany Street and Anzac Avenue in 1934. In 1944, a rehabilitation centre for disabled servicemen opened. Most of the other new land was put to industrial use. Dominion Industries built a linseed oil operation, Shaw Savill Albion a wool and grain store, J. Mill & Co. another wool store, and stationers Williamson Jeffery a factory and head office. On the north side of Leith, a new milk treatment station opened in 1948.

The dairy co-op secured a leasehold section from the Harbour Board in October 1945. Allan Cave, a North Island architect with extensive experience of dairy buildings, prepared preliminary sketch plans and a well was bored on the site in April 1946. Two months later, the district building commissioner deferred issuing a permit, due to the post-war building restrictions and a shortage of cement and labour.

In September 1946, Cave recommended switching to a local architect, and the company appointed L.W.S. Lowther in his place. Lowther immediately began work on plans and specifications, completed in February 1947.

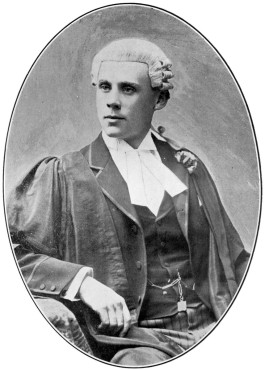

Born in Llanelli, Wales, to a New Zealand-born father, Lance Lowther had worked as assistant to Henry McDowell Smith before taking up private practice in 1945. He had at least a hand in many streamlined designs that came out of Smith’s office in the late 1930s, including the Law Court Hotel and two blocks of flats on View Street. In a more traditional aesthetic, he had a significant and it has been claimed leading design role (under Smith’s name) for the new St Peter’s Anglican Church at Queenstown. Early houses by Lowther include a Moderne/Art Deco design at the corner of Taieri Road and Wairoa Street. He later worked in private partnership with former Otago Education Board architect Clifford Muir.

Huia advertisement from the Otago Daily Times, 27 May 1949 p.7. Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

The construction history of the factory highlights the challenges faced in post-war building. Plans had to be approved by both the Department of Agriculture and the Harbour Board, both of which asked for changes. Finance also proved difficult, as although commercial banks were happy to lend, the Reserve Bank could exercise its power to stop advances of more than £60,000 for building work. Building firms were stretched and unenthusiastic to tender for the contract, but Love Construction gave a price from the quantities. They were given the go-ahead in August 1947, before the building controller again deferred issuing a permit. Despite repeated efforts it was not until February 1951 that a permit was finally issued. Drawings held in the Hocken are undated, but the work finally begun in March 1951 was probably mostly carried out according to the 1947 plans.

Michael Findlay has described the building as ‘constructed from steel reinforced concrete with steel roof trusses enabling wide spans and unobstructed floors. The wall and floor surfaces had rounded internal corners for hygiene and the design was efficient and modern, a great step up from their earlier Dunedin factory’. The Moderne exterior is characterised by clean lines and simplicity. It might also be described as Art Deco, as it fits some definitions of that style. Embellishment is minimal, consisting mostly of raised banding or string courses. Glass bricks are a feature of the west elevation, and allowed a filtered light into the factory.

The original plans show a large butter and smaller cheese manufacturing area, and a big garage space at the rear with access from Anzac Avenue. There was also stores, freezers, a box and pallet area opening to the cart dock on Parry Street, dressing rooms, and a dining room. Unusually, a bicycle parking area was placed internally in the south-west corner. Office activities took place upstairs, where there was a public counter, large general office, manager’s and secretary’s offices, strong room, another dining room, and a generously sized and wood-panelled board room.

Rosemarie Patterson’s excellent history of Naylor Love, A Bob Both Ways, provides some insight into experiences on the building site through the recollections of foreman Duncan McKenzie. He remembered laying the foundations on the swampy reclaimed site in the winter of 1951: ‘It was just an absolute bog. We were building a kind of floating foundation, big pads right across. 8 feet wide and 18 inches deep. Alex Ross, manager at the time, put an ad in the paper for labourers’. Because of the strike there were many men looking for work. ‘He started sending them to me, and they just kept on coming. But in those days we worked in the rain, and wharfies weren’t used to working in the rain, so most of them left on those wet days. A few stayed on, three or four who didn’t get their jobs back on the wharf.’

The project employed many new Dutch migrants. Conditions in Europe and a shortage of workers saw significant Dutch immigration after the Second World War, with over 10,000 arriving in the three years from July 1951 to June 1954. Most were single, non-English speaking men from a working class background, including carpenters and skilled labourers. McKenzie used one of his steelworkers, a good English speaker who had been a corporal in the Dutch Army in Indonesia, as an interpreter. McKenzie remembered they ‘had to learn to do things differently, especially the concrete work which all had to be boxed. They were not used to doing that.’

McKenzie also recalled Love’s purchasing their first skilsaw in time for the laying of the upstairs floor. ‘It was big 6 x ¼ inch flooring, and they brought it over for us to cut the flooring with. And everybody’s eyes nearly popped out. Len Griffin, the supervisor who used to go round the jobs, every so often for some particular job would come and borrow our skilsaw! The company’s only skilsaw! It was the same with dumpy levels. Being a big job, I always had one there, but there was always someone coming and borrowing it. We didn’t have one for a job, we had one for a lot of jobs.’

‘We didn’t have cranes. We had electric hoists. You’d fill the barrows, generally on the ground, and take them up on a hoist, and wheel the concrete round to wherever you wanted it, and pour it, and take it back down again. It got a bit more complicated later on. We’d take a skip on the hoist and put it in a hopper on the top. And you’d fill your barrow out of that. All the concrete was done by barrow. You had to have scaffold ramps up every lift. Every four feet you’d probably put a pour. So the scaffold had to be built at the right height to swing the barrow and tip the concrete in. We had pre-mix concrete there, but before that – while I worked on the Nurses’ Home in Cumberland Street – all the concrete was mixed on site.’

When construction began, co-op management optimistically hoped it would be able to its machinery in by April 1952, but there were more delays, including sourcing the roofing material and steel girders. In March 1953, the manager reported a shortage of carpenters. The building neared completion the following summer, but it was practically impossible to move in during the dairying season. In April 1954, building work was complete with the exception of some painting and plastering. Plant was moved from the old premises, and by the end of August all departments had moved in. The final build cost was £150,000.

Loading finished products. Campbell Photography. Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena P1998-167-004.

The building officially opened some eight years after the first consent permit was sought. Keith Holyoake, minister of agriculture and future prime minister, performed the honours before a crowd of 450 people on 2 November 1954. Referring to the end of the bulk purchasing agreement with the United Kingdom, he said: ‘This is a new era and a really challenging time as far as the primary producer is concerned’. In a peculiar call to arms for securing market share he said ‘we now have to fight the battle with the British housewife’.

The company had 55 staff in its Dunedin and Oamaru factories in 1954. Its products over the years included butter, process cheese, savoury sandwich paste, and reconstituted cream. A subtle name rearrangement occurred in 1976, when the Co-operative Dairy Company of Otago became the Otago Co-operative Dairy Company. In the 1980s the Dunedin factory was producing over 3,500 tonnes of butter annually.

Cheese continued to be made on the site, with a specialty cheese unit established in 1985/86. The company had large shareholdings in the Otago Cheese Co., and in Mainland Products Ltd, which had some operations at Anzac Avenue. In 1989/90 butter reworking ceased after the Dairy Board decided it could satisfy the Otago and Southland markets with patted butter ex-churn from Westland. In the same year, Mainland’s processing plant moved to Eltham, reducing manufacturing operations at Anzac Avenue to creamery and whey butter, and specialty cheese. A Cheese Shop fronting Parry Street opened in 1990, with some products continuing to be marketed under Huia brand. Adjoining chicken and sausage shops also operated for a time but were less successful. The company performed well for its shareholders, but the Anzac Avenue site was becoming surplus to requirements.

Reconstituted cream point of sale advertisement. Ref: Otago Co-operative Dairy Company records, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena 84-159/003.

The building as it appeared in 1997, when vacated by the dairy company. Ref: Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena MS-4069/070.

The University of Otago purchased the building in 1996, for redevelopment as a new Hocken Library. The library had been established in 1910 to care for and provide access to Dr Thomas Morland Hocken’s public gift of his collection of books, pamphlets, newspapers, maps, paintings, and manuscripts relating to Aotearoa New Zealand and the Pacific. It opened in a purpose-built wing of the Otago Museum and was a much expanded collection by the time it left that site in 1979. By the 1990s the collections were split between the Hocken (now Richardson) Building and a former vehicle testing station in Leith Street. The dairy co-op site brought the library, archive, and gallery together in a secure, environmentally controlled facility, and allowed much improved public access. The architects for the redevelopment were Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates in collaboration with Works Consultancy Services, and the project was managed by Octa Associates Ltd. The main contractor was Lund South.

The University took possession on 30 June 1997 and the work was carried out over most of 1998. The interior was more or less gutted, with the reorganised space including a large foyer, gallery, public reference area, reading rooms, public lunch room (now researcher lounge), staff areas, and stacks. Preserved internal features included steel trusses and exposed timber joists. Two doors with frosted-glass decoration (moved from the entrance) each feature a pair of huia, as used in the co-op’s branding. The building retains the sympathetic colour scheme given to it at this time, of yellow-creams and gold, with grey-green metal joinery. One of the more obvious external changes was the replacement of steel-framed windows with aluminium ones.

Officially opened by Governor General Sir Michael Hardie Boys on 2 December 1998, the refurbished building was the university’s major Otago sesquicentennial project. It is currently home to over 11 shelf kilometres of archives, 200,000 books, 17,000 pictures, and 2 million photographs, bringing it to very near capacity.

The Hocken Library, in case there is confusion, remains the official name for the building, while the institution within is the Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, a branch of the University of Otago Library.

The building during its transformation into the Hocken Library in 1998. Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena MS-4069/070.

After selling its building, the Otago Co-operative Dairy Co. did not continue as an independent entity for long. The profitable business made a record payout to shareholders in 1996 but mergers across the industry meant there would only be four co-operatives nationwide by the end of the 1990s, and a further mega-merger would follow. In 1997, Otago merged into Kiwi Co-operative Dairies. One farmer who welcomed the news commented: ‘Otago is sitting as a small company doing well and wondering where it will end up’. In 2001, Kiwi in turn merged with the New Zealand Dairy Group and the New Zealand Dairy Board to form the country’s largest company, Fonterra. The Anzac Avenue building is now one of few tangible reminders of the old business.

Newspaper references:

Lyttelton Times 16 October 1873 p.3 (‘A Cheese Factory in Otago’, copied from Otago Guardian); Evening Star 29 April 1920 p.6 (advertisement for Huia butter), 8 September 1922 p.2 (formation of company), 25 November 1922 p.4 (Loudon’s proposal), 17 May 1923 p.9 (proposed highway), 7 July 1923 p.4 (housing proposal), 14 November 1924 p.2 (‘Highway proposal’), 11 May 1928 p.5 (trees and verges), 29 April 1933 p.23 (dead trees), 2 August 1934 p.12 (elms, with photograph), 5 August 1936 p.14 (elms), 9 August 1937 p.11 (elms) , 10 August 1938 p.15 (elms), 16 September 1938 p.7 (replacing damaged trees); Otago Daily Times 12 October 1922 p.5 (notice of establishment), 22 October 1923 p.9 (‘famous Huia butter’), 19 June 1928 p.18 (company history and purchase of Dunedin Dairy Co.), 9 March 1934 p.6 (dead and stunted trees), 30 September 1942 p.6 (‘Butter business purchased’), 5 August 1947 p.6 (‘New factory to be built’). 3 November 1954 p.10 (‘New £140,000 dairy facory opened by Mr K.J. Holyoake), 21 March 1996 p.1 (‘Dairy factory to become Hocken Library’), 31 July 1996 p.16 (‘Otago Dairy Co-op makes record pay-out to suppliers’), 30 October 1997 p.3 (‘Otago-Kiwi dairy merger nets suppliers a windfall’ and ‘Dairy merger welcomed by farmers’)

Books:

Ledgerwood, Norman. Southern Architects: A History of the Southern Branch, New Zealand Institute of Architects (Dunedin: Southern Branch, New Zealand Institute of Architects, 2009) p.126.

Patterson, Rosemarie. A Bob Both Ways: Celebrating 100 Years of Naylor Love (Dunedn: Advertising and Art, 2010), p.90.

Philpott, H.G. A History of the New Zealand Dairy Industry 1840-1935 (Wellington: Government Printer, 1937), pp.375-406 (statistics).

Web resources:

Petchey, Peter. ‘La Crème de la Crème‘, Friends of the Hocken Bulletin no.26 (November 1998), https://www.otago.ac.nz/library/hocken/otago038951.html#bulletins (accessed 24 October 2019).

Stringleman, Hugh and Frank Scrimgeour, ‘Dairying and Dairy Products‘, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/dairying-and-dairy-products (accessed 24 October 2019).

Yska, Redmer, ‘Dutch – Migration After 1945‘, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/dutch/page-2 (accessed 24 October 2019).

Zam, Darian, ‘When Lactose Goes‘, Longwhitekid, https://longwhitekid.wordpress.com/2011/05/31/when-lactose-goes/ (accessed 24 October 2019).

Archives:

Otago Co-operative Dairy Co. records, Hocken Archives, including manager’s reports (84-159 box 6), architectural drawings (97-235 box 32), and annual reports (97-235 box 4).

Special thanks to: Chris Naylor, Rosemarie Patterson, Barbara Parry, Chris Scott (DCC Archives), and the late and much missed Michael Findlay.