Built: 1873

Address: 90-108 Princes Street

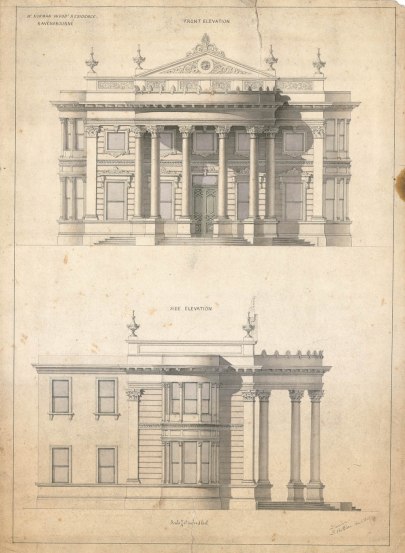

Architects: Mason & Wales

Builders: Wood & Steinau

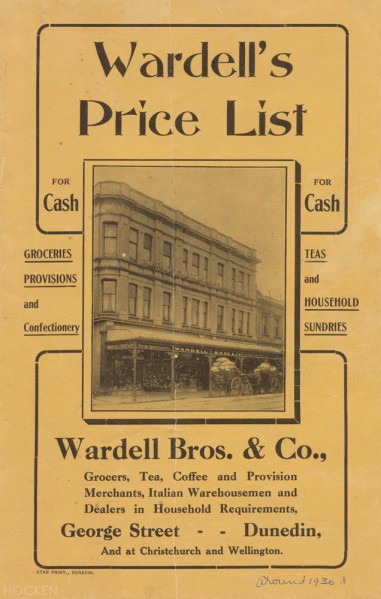

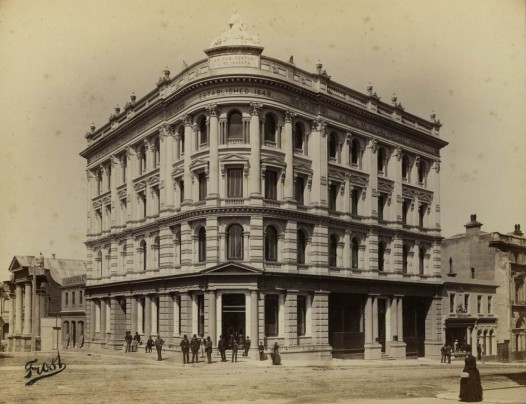

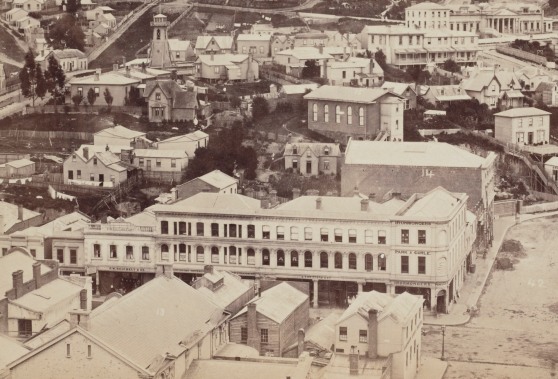

The buildings as they appeared c.1907. Ref: Collection of Toitu Otago Settlers Museum, Box 57 Number 200.

Since the demolition of its northern neighbour in the 1980s, the facade of 100-108 Princes Street has come to a slightly raggedy end, and the off-centre word ‘Hotel’ has looked a bit peculiar without the word ‘Central’ that once followed it. Although the two buildings that formed the Hotel Central had an integrated facade, they were separated by a party wall and had distinct roof structures. They were even built under separate contracts for different clients.

The surviving portion was built for the drapers Thomson, Strang & Co., and the demolished one for Dunning Bros. Built in 1873, the buildings replaced wooden structures that were only about ten years old, but which in a period of rapid development were already seen as the antiquated stuff of pioneer days. The architects were Mason & Wales and the contractors Wood & Steinau.

The buildings were described in the Otago Daily Times as ‘very handsome’ but it was remarked that ‘their elevation and length appear to be altogether out of harmony with the irregularity of the comparatively small structures opposite’. The facade originally featured a bracketed cornice and most of the first-floor windows were hooded. Stone was used for the foundations and ground floor, and brick for the upper floors.

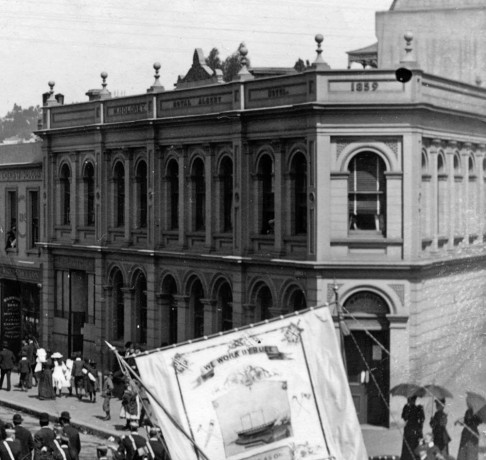

Detail from a Burton Bros panorama, showing the buildings as they appeared in 1874, not long after their completion. Ref: Te Papa C.025695.

Who were the Dunning brothers? Alfred Theodore Dunning and Frederick Charles Edward Dunning were English settlers who started out as fruiterers in Princes Street in 1864. Frederick left the partnership in 1871, but did return for a few years later in the decade. In 1874 Alfred was granted a license for the City Dining Rooms, which he opened upstairs in the new building. He established a hotel across the upper floors of both buildings, and from 1878 the establishment was known as Dunning’s Central Hotel and Café. The portion above the drapery contained bedrooms, while rooms in the northern part included a dining room, offices, and a large billiard room.

Alfred was known for his joviality, uprightness in business, and warm-heartedness, but although he did well in the hotel business he was less successful when he left in 1881 to take up theatrical management. He lost most of his money in opera ventures and died in Melbourne in 1886 at the age of 41. Frederick became a fruiterer in Christchurch, where he died in 1904 after falling from his cart.

The drapery firm Thomson, Strang & Co. had started out as Arkle & Thomson in 1863. J.R. Strang became a partner in 1866 and the firm operated from its new premises for just under ten years, closing in 1883. From 1885 to 1928 the ground floor of this southern end of the buildings housed Braithwaite’s Book Arcade. Joseph Braithwaite had established his business in Farley’s Arcade in 1863 before the move to Princes Street. The store had a horseshoe-shaped layout that extended into Reichelt’s Building on the south side, and the horseshoe theme was carried through to distinctive frames over the two entrances. It was claimed over 10,000 people once visited the arcade on a single day, and Braithwaite’s became so well-known that it was considered a tourist attraction. It was a popular place to shelter from bad weather, and everyone from unchaperoned children to the local business elite might be seen browsing the shelves. By 1900 the business employed thirty sales men and women. The footprint of the arcade changed a few times as it moved in and out of neighbouring shops.

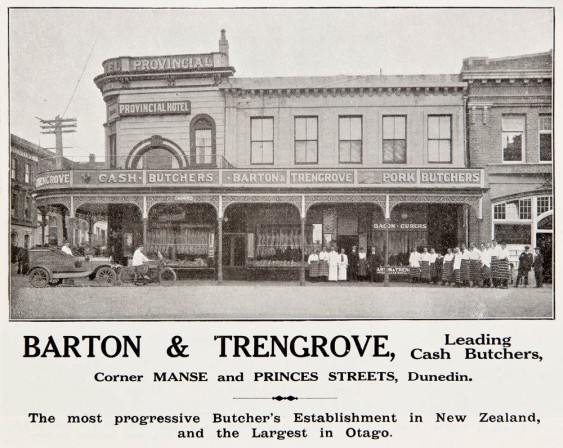

Detail from c.1907. At the centre is the lamp for Haydon’s Central Hotel. On the left is one of the entrances to Braithwaite’s Book Arcade. The shop on the right was occupied by the jeweller James Bremner. Note the pilasters with their Corinthian capitals. Ref: Collection of Toitu Otago Settlers Museum.

The Central Hotel’s license was transferred to John Golder in 1881, and he reportedly installed one of the largest plate glass windows in the colony. He was succeeded by Robert T. Waters, who changed the name to the Baldwin Hotel, perhaps after the celebrated hotel of the same name in San Francisco. After Waters came Charles Nicholson, James D. Hutton, and Thomas Cornish. During Cornish’s time the name changed back to Central Hotel, and later licensees were James Macdonald, E.J. Power, William H. Haydon, and Catherine J. Haydon. The license was lost in 1909, and the establishment afterwards continued as a private hotel and boarding house. It was known as Jackson’s Hotel from about 1922 to 1936, when it became Hotel Central.

The hotel featured in an unusual example of pioneering photography, for Dunedin at least. In 1903 a couple were photographed in a bedroom of the City Hotel from an opposite room in the Central Hotel, and the evidence was used in a divorce case. The respondent claimed she was only playing cards with the co-respondent, whom she described as an elderly, very short, stout, bald-headed, and not at all good-looking friend. The jury were unconvinced and a divorce was granted.

Tragedy occurred in 1900 when William O’Connell, a 76-year old miner from Nevis, died after falling from one of the rear windows during the night, into the yard below.

From 1916 the buildings included the entrance to the Empire Theatre (a cinema), complete with terrazzo flooring and marble mosaics. In 1935 the theatre’s entrance was moved from Princes Street to Moray Place, and two shops were built in the place of the old entry.

The history of the shops is complex as over one hundred businesses have operated from them over the years, and partitions were sometimes put up to turn a large shop space into two smaller ones, or taken down to restore a larger space. Most of the businesses that were in the buildings for five years or more are in the list below. The dates are mostly compiled from directories and newspapers advertisements and so are only an approximate.

Thomson, Strang & Co. (1873-1883)

Raymond & Howard, chemists (1874-1884)

J. Wilkie & Co., stationers etc. (1879-1885)

August Fettling, jeweller (1880-1885)

Alexander Allen, tobacconist (1883-1896)

Stewart Dawson & Co., jewellers (1884-1891)

Alex W. McArthur, jeweller and optician (1888-1894)

William Macdonald, hosier (1889-1894)

William Reid, florist (1894-1907)

J.J. Dunne, hosier and hatter (1896-1906)

James Bremner, jeweller and optician (1898-1914)

William Aitken & Sons, tailors (1902-1907)

Elizabeth Rodie, draper (1906-1919)

E.H. Souness, watchmaker and jeweller (1908-1915)

Elite Tea Rooms (1915-1973)

Sucklings Limited, photographic specialists (1919-1931)

Watkins & Neilson, mercers and tailors (1922-1927)

The Horse Shoe, fancy goods dealers (1928-1934)

Adams Bruce Ltd (1928-1935)

Piccadilly Shoppe, lingerie specialists (1928-1982)

‘The Ideal’, frock and knitwear specialists (1930-1988)

Marina Frocks (1935-1954)

Cameron’s Central Pharmacy (1935-1985)

Tip Top Milk Bar (1935-1955, succeeded by the City Milk Bar 1955-1961)

E. Williams, toilet salon (1936-1944)

Johns of London, beauty specialists (1944-1956)

Newall’s Chinaware (1954-1972)

London House, menswear (1957-1967)

Carlton Bookshop (1962-1984)

Rob’s Wool Shop (1972-1986)

Southern Cross Jewellers (2002-2015)

Some businesses moved to different shops within the buildings, including Sucklings (around 1928) and the Ideal (around 1954). The Tip Top is perhaps a surprise inclusion on the list – the ‘no.2 shop’ was here while the more widely remembered ‘no. 1’ operated from the Octagon corner.

One of the longest-lasting enterprises in the buildings was the Elite Tea Rooms. Established by Hannah Ginsberg as the Elite Marble Bar in 1915, it advertised a tastefully decorated lounge room, a menu of fifty different iced drinks and ice creams, and a wide range of hot drinks including coffee, Bovril, and Horlick’s. For many years, from 1919 onwards, it was run by Jean Dunford and Sarah Mullin, and the business remained on the site until about 1973.

Advertisement from the Evening Star, 8 November 1919 p.6

A 1960s view

The facades were stripped of their Victorian decoration in 1952 and remodelled to the designs of architect L.W.S. Lowther, incorporating late use of the Art Deco style. The name ‘Hotel Central’ was added in plain sans serif capitalised relief lettering at the parapet level. Directories and advertising suggest that the names ‘Hotel Central’ and ‘Central Hotel’ were sometimes used interchangeably. The private hotel’s last entry in Wise’s directory was in 1977, but it would be could to pin down the date of its closure more accurately.

The northern building was demolished in 1987 to make way for additions to the Permanent Building Society building (now Dunedin House). This was remodelled in the postmodern style fashionable in the 80s, and its new features included tinted and mirrored glass, supersized pediments, and shiny columns. The older building now looks cut in half, but the changes made to the facade in the 1950s have exaggerated that effect. It recently changed ownership, so perhaps more change is in store in the not distant future.

The surviving building in 2016

Newspapers references:

Otago Daily Times, 1 August 1873 p.1 (call for tenders), 8 August 1873 p.3 (demolition progress), 1 September 1873 p.2 (accident); 22 November 1873 p.3 (progress – ‘out of harmony’); 24 December 1873 p.1(grand opening); 6 June 1874 p.4 (opening of public dining room); 2 September 1874 p.3 (court dispute – contractors), 30 October 1873 p.2 (accident during construction), 3 February 1876 p.3 (Dunning Bros partnership notice), 18 November 1878 p.3 (Dunning’s Central Hotel advertisement), 26 May 1881 p.3 (to let, retirement of Dunning), 9 July 1881 p.2 (largest plate glass windows in the Colony), 21 November 1883 p.3 (winding up of Thomson Strang), 23 April 1900 supp. (Braithwaite’s Book Arcade), 26 September 1900 p.7 (fatal accident), 22 June 1909 p.4 (license refused), 4 March 1916 p.11 (Empire Theatre); Otago Witness, 13 June 1874 p.2, 4 (opening of dining rooms), 2 September 1874 p.3 (dispute); Evening Star, 22 October 1915 p4 (Elite Marble Bar), 16 April 1935 p.2 (theatre entrance replaced with shops).

Other references:

Stone’s, Wise’s, and telephone directories

Baré, Robert, City of Dunedin Block Plans. Dunedin: Caxton Steam Printing Company, [1889].

W.H. Naylor Ltd: Records (Hocken Collections AG-712/036), plans for 1952 remodelling.