Born: Ferrara, Italy, 9 April 1832

Died: Maldon, Victoria, Australia, 12 October 1908

While researching the Dunedin musician Raffaello Squarise ten years ago, I became intrigued by another Italian who featured large in Dunedin’s cultural history. Hardwicke Knight and Niel Wales had said that virtually nothing was known of him, apart from some major contributions he made to the city’s architecture. Peter Entwisle also lamented that so little was known, and through his ‘Art Beat’ column in the Otago Daily Times shared some new information I uncovered. I’ve been occasionally digging around ever since.

In the thirteen years he lived in Dunedin, Boldini gave the city some of its richest and most exuberant pieces of architecture. In the 1880s there were fewer than two dozen Italian-born people living here, and Boldini was the only Continental European architect in a profession that was dominated by Scotsmen and Englishmen, and only beginning to add the sons of colonists to its ranks. Many of these architects designed in the Renaissance Revival manner, but Boldini’s personal style had what Entwisle nicely describes as a ‘distinctively continental stamp’.

Luigi Boldini was born in Ferrara, where his father Antonio (1798-1872), was an artist known for painting religious subjects. His mother, Benvenuta Caleffi, had been a seamstress. Luigi was the couple’s eldest son, and the second of thirteen children. The family moved to the home of his grandparents, the Federzonis, in 1842. Luigi Federzoni (stepfather of Antonio) was a civil engineer and architect who had earlier worked as a cabinetmaker.

In 1846 the family inherited a house in the Via Borgonuovo, with a beautiful view of the Castello Estense. It had belonged to Luigi’s wealthy great-uncle, who had no children of his own. The uncle’s legacy favoured Luigi (who was also his godson) and granted him an annual pension which allowed him to study civil engineering in both Rome and Paris. One of Luigi’s brothers, Giuseppe, became a sculptor, and another, Gaetono, became a railway engineer. A third, Giovanni, became a fashionable and internationally famous portrait painter in Paris, and was known as ‘The King of Swish’ for his flowing style of impressionist-influenced realism. Luigi gave Giovanni much financial help in the early years of his career.

A patriot, Luigi was described as one of Garibaldi’s soldiers, and with his schoolmates Gaetano Ungarelli and Gaetano Dondi he participated in the successful defence of Ancona in 1849. By 1855 he was studying in Paris, where he was a contemporary of Gustave Eiffel, though probably at another institution. Following his graduation, he worked as a city engineer in Ferrara, and taught at the local technical institute. One of his early designs was a mausoleum for the Trotti family, built in 1855. The Copparo Town Hall was rebuilt from the ruins of the Delizia Estense palazzo between 1867 and 1875 to Boldini’s plans.

On 25 April 1861 Luigi married Adelina Borelli at Ferrara, and they had at least two sons and a daughter together. After the death of Adelina, Luigi decided to migrate to Dunedin, where he arrived aboard the Wild Deer on 20 January 1875, accompanied by his sons Gualterio (12) and Alfredo (7). It’s puzzling that an Italian engineer from a wealthy family chose to move to a settlement in one of the remotest of British colonies, even one that had experienced rapid development and offered good professional opportunities. Luigi suffered from a kidney condition, so perhaps he was one of the many people who were advised by their physicians to seek out the New Zealand climate for its supposed revitalising qualities. There may also have been personal or political reasons that made it untenable for him to remain in Italy, or perhaps like many others he wished to escape the difficult economic and social conditions in his own country.

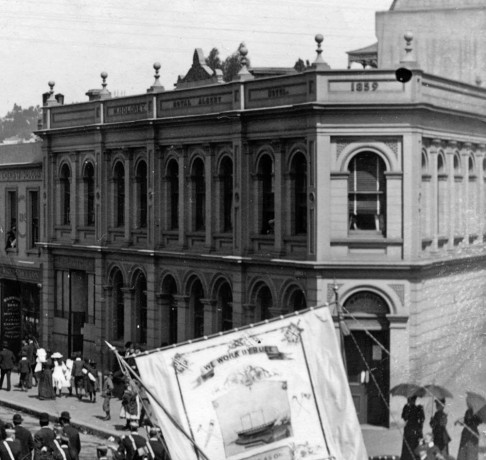

Albion Hotel, Maclaggan Street, Dunedin. Image: Otago Witness, 1 July 1903 p.44.

In Dunedin Luigi anglicised his name to Louis, and his sons became Walter and Alfred. Walter studied at the Otago School of Art from 1876 to 1877, where he was commended for his chalk drawings. He also attended Otago Boys’ High School, where he won drawing and writing prizes and was Dux of the Lower School. Louis kept a low profile during these years but joined the Otago Art Society. The earliest Dunedin building designed by him that I have been able to trace is the Albion Hotel in Maclaggan Street, built for Joseph Davies in 1877. A newspaper reporter admired the use of space and described the style as a mixture of French and Italian. Jobs in 1878 included brick offices for Keast & McCarthy (brewers) in Filleul Street, a coffee saloon for A. & T. Dunning (internal alterations), and a brick building in Heriot Row. The last may have been Sundown House, which Boldini advertised as his place of business.

-

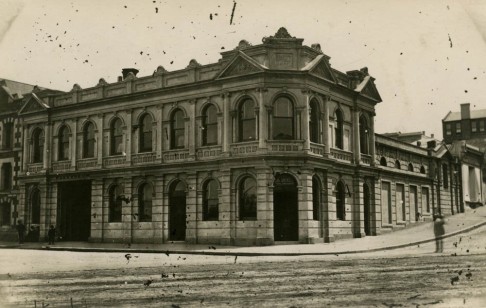

Newmarket Hotel, Manor Place, Dunedin. Image: Toitū / Otago Settlers Museum 80-85-1.

I have mainly identified Boldini’s Dunedin projects from tender notices in the Evening Star, a newspaper he preferred to the Otago Daily Times. These notices refer to over fifty projects, but there must have been many more for which the builders were found by other means. Boldini became particularly recognised as an architect of hotels, and the years 1879 to 1881 saw the realisation of his plans for the Rainbow Hotel, Cattle Market (later Botanic Gardens) Hotel, Martin’s (later Stafford) Hotel, London Hotel, Royal Albert Hotel, Peacock Hotel, and Newmarket Hotel. The style ranged from plain cemented facades with simple cornices and mouldings in the case of the Rainbow, to highly decorated Renaissance Revival designs for the Royal Albert and Newmarket. The latter two both made good use of sloping corner sites. The Newmarket featured Ionic pilasters and bold decorated pediments, but looked a little top-heavy due to the modest height of the lower level. Both hotels featured distinctive acroteria, decorative devices which became something of a signature for Boldini and which were not often used by other local architects.

Synagogue, Moray Place, Dunedin. Photo: Muir & Moodie. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa C.012193.

Detail of exterior, Synagogue, Moray Place, Dunedin. Image: Muir & Moodie, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa C.012193.

Synagogue, Moray Place, Dunedin. Image: Muir & Moodie. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa C.012364.

Detail of interior, Synagogue, Moray Place, Dunedin. Image: Muir & Moodie. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa C.012364.

On 20 July 1880 Boldini won a major commission, when he saw off rival T.B. Cameron with his design for a new synagogue in Moray Place. The Dunedin Jewish Congregation no longer found its 1860s building convenient, and spent £4,800 on an imposing and lavishly-appointed replacement. The architecture was Classical, and featured a portico supported by large pillars with impressive Corinthian capitals. Diamond-shaped carvings on the front door panels were reminiscent of the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara, and iron railings designed by Boldini were made by Barningham & Co. The completed building was consecrated on 28 August 1881.

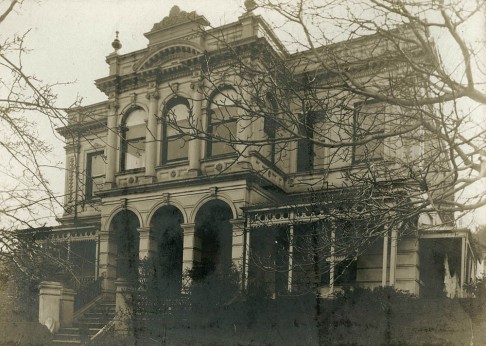

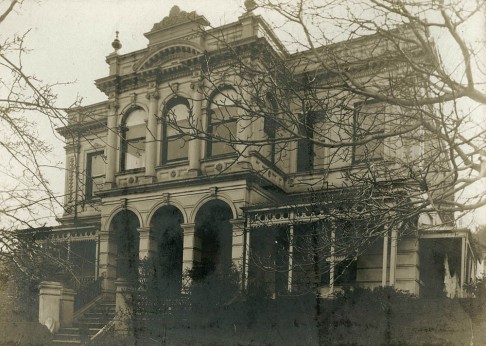

In the same year Maurice Joel, President of the Jewish Congregation and Chairman of its Building Committee, commissioned Boldini to design additions to his own house in Regent Road (which had been designed by David Ross). Boldini’s design added steps and a striking central bay with a loggia (an unusual feature in Dunedin) and an elaborately ornamented parapet.

Eden Bank House, Regent Road, Dunedin. Image (c.1905): Hocken Collections S12-549c.

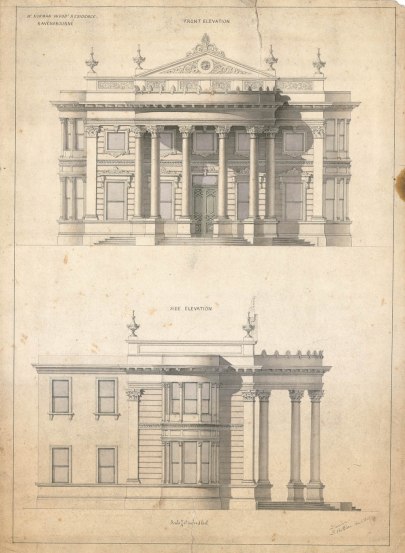

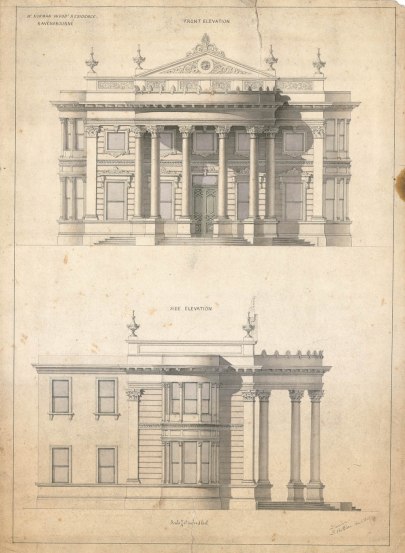

Elevation drawings of proposed residence for Norman Wood, Ravensbourne. Image: Hocken Collections, Owen MacFie papers, MS-1161/256.

Boldini’s other projects of 1879-1881 included refreshment rooms at the Clinton Railway Station, a large block of commercial buildings for Herman Dodd at the corner of George Street and Moray Place (now the site of the Westpac building), shops for William Cranston (St Andrew Street) and John Mulrooney (Stafford Street), and the Oddfellows’ Hall for Norman Wood at Ravensbourne. Wood was a building contractor and served as Mayor of West Harbour, he also commissioned Boldini to design a grand residence at Ravensbourne but this was never built, likely due to Wood’s financial position (he went into bankruptcy a number of times). A proposed Town Hall for West Harbour was also abandoned, but the South Dunedin Town Hall was built to Boldini’s design. Unfortunately, his residential buildings are hard to identify, as most of the tender notice descriptions are vague. There were two houses for William Lane in Melville Street, a brick villa in Abbotsford, a cottage in North East Valley, a brick house in Caversham, and a residence in Cumberland Street. There was also brick house built in Clyde Street in 1881, which may have been Sir James Allen’s residence ‘Arana’. Boldini designed ‘Dulcote’ in the same street for Allen’s brother, Charles, in 1886.

Most of the work was for brick buildings, but work in timber included shops and houses built at St Kilda in 1880.

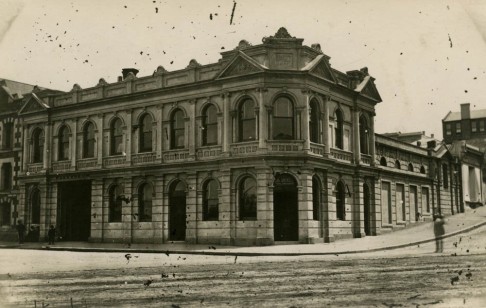

Grand Hotel, High and Princes streets, Dunedin. Image: Toitū / Otago Settlers Museum, 80-74-1.

If there was any doubt that Boldini had secured a reputation as one of Dunedin’s leading architects, this was put to rest in 1882 when he was commissioned to design the Grand Hotel for James and John Watson. The Grand was the largest and most lavishly appointed hotel in New Zealand. Designed ‘in many respects after approved American and European models’, its mod cons included speaking tubes, bells, electric lighting, and a passenger lift. The Oamaru stone facade gently curved at the street corner, and was decorated with ornate carving by Louis Godfrey. For some of the internal plaster decoration Boldini sent his designs to England for manufacture, and large iron columns were cast by Sparrow & Co. Concrete and iron were used for the shell of the building and the floors, which were designed to be as fire proof as possible. The hotel opened on 6 October 1883, when 6,000 people visited. The building contractor was James Small and it cost over £40,000 to build.

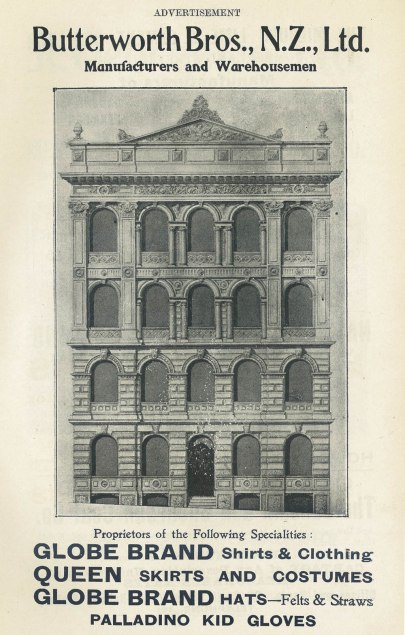

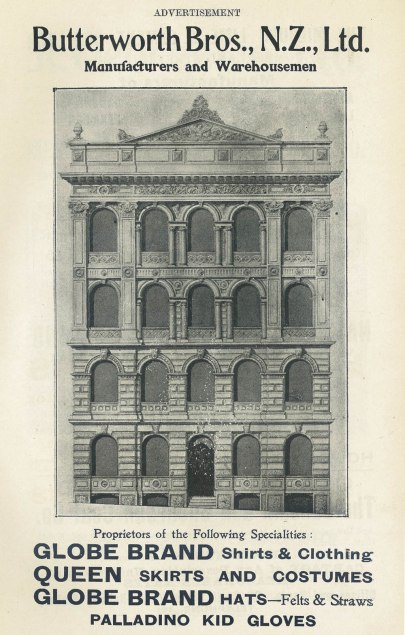

Butterworth Bros warehouse, High Street, Dunedin. The facade was remodelled in the late 1940s and the building was demolished in 2010. Image: Advertisement from ‘Beautiful Dunedin’ by W.H. Fahey (1906).

Parkside Hotel, South Road, Dunedin. The building survives but the frontage was extended in 1925 and given an entirely new facade designed by Edmund Anscombe. Image (189-): William Williams, Alexander Turnbull Library 1/2-140504-G.

Boldini’s largest warehouse design was for Butterworth Brothers, importers and manufacturers of clothing and other soft goods. Some of this firm’s wealth might have been better directed at the working conditions of its employees, as the company was one of those named and shamed in the sweated labour scandal that broke in 1889. Most of the building was brick, with the facade constructed from Port Chalmers and Oamaru stone and elaborately carved. ‘Fire proof’ floors were again constructed with iron beams and concrete.

Other work by Boldini between 1882 and 1885 included the fitting out of the Parkside Hotel in South Road, interior work for the City Butchery, a stone homestead at Tarras, two houses at St Clair (a wooden cottage and a brick residence), a wool shed for M.C. Orbell at Whare Flat, and a house at Dunback for T.E. Glover.

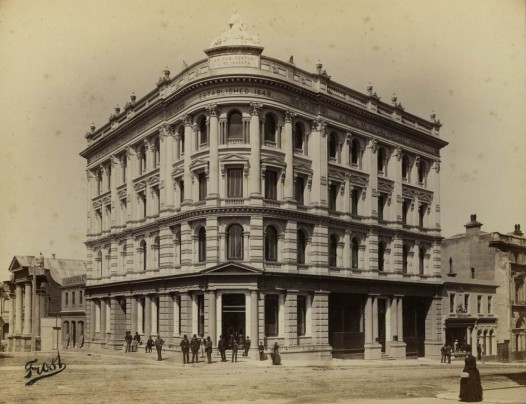

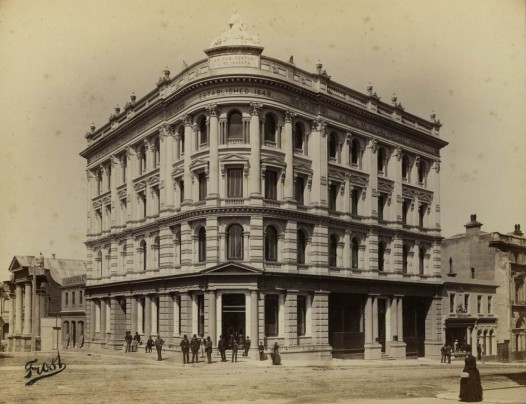

AMP Building, Princes and Dowling streets, Dunedin. Image: Frost, Toitū / Otago Settlers Museum 32-49-1.

Boldini’s last major design in Dunedin was built for Australian Mutual Provident Society on the corner of Princes and Dowling streets. Announced in January 1886, its generous proportions were very noticeable when its four storeys were compared with the modest two-storey buildings on either side. The contractor was again James Small, who tendered a price of £21,600. Some of the policyholders objected to the extravagance of the building, which took two years to build. The ground floor facades were built of Port Chalmers stone with Carrara marble pilasters, and the upper floors were Oamaru stone, with granite columns on the top floor. Interior materials include Abroath stone, Minton and majolica tiles, wrought iron pillars, and cedar woodwork. The top floor was a clothing factory, operated by Morris and Seelye, and which accommodated 100 young women. It was one of Dunedin’s greatest architectural losses when this building was destroyed in the summer of 1969-70. The demolition job took much longer than planned, as it was discovered that Boldini has been something of a pioneer in structural reinforcing.

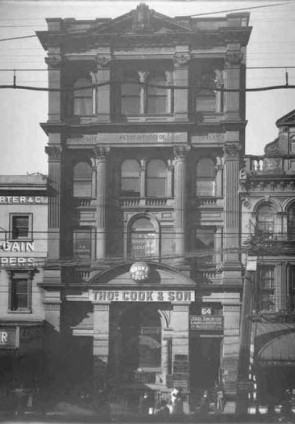

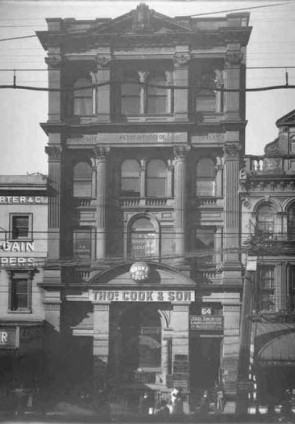

In September 1886 Boldini gained a commission in Auckland, for the Mutual Life Association of Australasia. With a contract price of £11,000, it was just over half the cost of the AMP offices, reflecting its smaller size. It was completed in December 1887, well ahead of the AMP, which was not finished until August 1888. For over a year Boldini had two very large jobs at opposite ends of colony and this involved much travel, although Mahoney & Sons were supervising architects for the Auckland building. Boldini also gained a daughter-in-law during this period, with his son Walter marrying Jane Wilson at a Dunedin Registry Office on 4 June 1887. Both Walter and Alfred settled in Australia.

Louis was in Dunedin for the testing of the lift in the AMP Building on 8 March 1888, and the following day he left for Australia on board the Rotomahana. I have found no evidence that he ever returned.

Mutual Life Association of Australasia, Queen Street, Auckland. Image: Henry Winnkelmann. Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 1-W1393.

Postcard showing Karori, Mount Macdeon. Image: courtesy of Dominic Romeo.

Karori, Mount Macdeon. Image (2013): courtesy of Dominic Romeo.

Karori, Mount Macdeon. Image (2013): courtesy of Dominic Romeo.

By 1888 building activity in Dunedin was at a low ebb, and the colony as a whole suffering the effects of the long depression. An opportunity presented itself in Australia, when former Wellington businessman Charles William Chapman asked Boldini to design a summer retreat at a bush station on the southern slopes of Mount Macedon, Victoria. Splendidly restored by Dominic and Marie Romeo between 2011 and 2013, it has been described as a ‘Swiss Chalet’ style building, and its square tower brings out an Italianate character. It has been suggested that some of the external fretwork draws from Maori design, but if so the interpretation looks quite free.

Chapman was an investor in a syndicate led by Dr Duncan Turner, which built an immense guest house resort building at Woodend between 1889 and 1890. With 50-60 rooms and a building area of 2,130 square metres, this was the largest timber structure Boldini designed. Its influences have been described as Venetian, Swiss (the chalet again), Californian (as in trade publications popular at the time), and New Zealand (with its many timber villas). The fretwork on Braemar is highly elaborate, and the octagonal corner tower is a grandiose but delightfully romantic feature.

Lithograph depicting Braemar, Woodend. Image: private collection.

Braemar, Woodend. Image: State Library of Victoria b52993.

Mechanics’ Institute and Free Library. Image (2011): Mattinbgn (Creative Commons).

For a time Boldini lived in Melbourne and Daylesford. He settled in Maldon around 1896, a town with a population of about 1,600 residents. He opened an office in High Street, and buildings from this last phase of his career show some change in his style, following the fashion for greater use of unrendered brick, and continuing the development of his domestic timber designs. His Mechanic’s Institute and Library in Woodend with its cemented Renaissance Revival facade is perhaps the closest to his Dunedin aesthetic. Boldini’s surviving buildings in Maldon include the residence Minilya, the Scots’ (Presbyterian) Church, Phoenix Buildings, and various works for Maldon Hospital, including additions to the main building and remodelling. Two designs, a Benevolent Ward for the hospital and the Maldon Hotel, were not completed until after his death.

Boldini was involved in community affairs, and was made a life governor of the Maldon Athenaeum for the service he gave to that society. He died in Maldon on 12 October 1908, after being admitted to hospital with chronic cystitis and uraemia. A Presbyterian minister presided over his burial at the local cemetery, and his grave is unmarked.

-

Minilya (Calder residence), Maldon, Victoria. Image (2011): Courtesy of Jan Warracke.

Scots’ Church, Maldon. Image (2011): Mattingbn (Creative Commons).

Phoenix Buildings, Maldon, Victoria. Image (2009): City of Greater Bendigo, Macedon Ranges Shire Council.

Maldon Hotel, Victoria. Image (2009): City of Greater Bendigo, Macedon Ranges Shire Council.

So far no photograph of Boldini has emerged. His brother Giovanni was five foot one inches tall, and a dapper moustachioed society figure, but the two men may not have looked very similar. I hope to put a face to this story one day.

Boldini’s built legacy has fared better in Australia than in New Zealand. In Dunedin, three of his four grandest designs have been demolished: the AMP Buildings (1969-1970), the Synagogue (1972), and Butterworth Bros’ warehouse (2010). There is some irony that the Butterworth building was demolished by the owners of the remaining building, the Grand Hotel, to make way for a car park. Hopefully further research will identify more buildings and more about the man behind their design.

Boldini’s unmarked grave in Maldon Cemetery. Image (2013): courtesy of Jan Warracke.

Selected works:

- 1877. Albion Hotel, Maclaggan Street, Dunedin

- 1878. Coffee salon for A. & T. Dunning, Princes Street, Dunedin.

- 1878. Keast & McCarthy offices, Filleul Street, Dunedin

- 1879. Rainbow Hotel, George and St Andrew streets, Dunedin

- 1880. Royal Albert Hotel, George Street, Dunedin*

- 1880. Cattle Market Hotel, North Road, Dunedin

- 1880. Martin’s Hotel, Stafford Street, Dunedin

- 1880. London Hotel, Jetty Street, Dunedin

- 1880. Oddfellows’ Hall, Ravensbourne

- 1880. Refreshment rooms, Clinton Railway Station

- 1880-1881. Synagogue, Moray Place, Dunedin

- 1880-1883. Dodd’s Buildings, George Street and Moray Place, Dunedin

- 1881. Brick residence (Arana?*), Clyde Street, Dunedin

- 1881. Peacock Hotel, Princes Street, Dunedin

- 1881. South Dunedin Town Hall, King Edward Street, Dunedin

- 1881. Newmarket Hotel, Manor Place, Dunedin

- 1881. Additions to Eden Bank House (Joel residence), Regent Road, Dunedin

- 1882-1883. Grand Hotel, High and Princes streets, Dunedin*

- 1883. Butterworth Bros warehouse, High Street, Dunedin

- 1883. Parkside Hotel, South Road, Dunedin*

- 1884. Homestead (stone), Tarras

- 1884. Additions to Fernhill, Melville Street, Dunedin

- 1885. Woolshed for M.C. Orbell, Whare Flat

- 1885. Glover residence, Dunback

- 1886. Dulcote, Clyde Street, Dunedin

- 1886-1888. AMP Building, Princes and Dowling streets, Dunedin

- 1886-1887. Mutual Life Association building, Queen Street, Auckland

- 1888. Karori (for C.W. Chapman), Mount Macdeon, Victoria*

- 1889-1890. Braemar, Woodend, Victoria*

- 1893. Mechanics Institute and Library, Woodend, Victoria*

- 1894. Bath house, Hepburn Springs, Victoria*

- 1896-1897. Additions and remodelling, Maldon Hospital, Victoria*

- 1899. Dining room, Maldon Hospital, Victoria*

- 1900. Minilya (Calder residence), Maldon, Victoria*

- 1905-1906. Scots’ Church, Maldon, Victoria*

- 1906. Phoenix Buildings, Maldon, Victoria*

- 1907-1909. Maldon Hotel, Maldon, Victoria*

- 1909. Benevolent Ward, Maldon Hospital, Victoria*

*indicates buildings still standing

Primary references:

Too many to list here, many from newspaper sources available online through PapersPast and Trove, and from the Evening Star (Dunedin) on microfilm. Feel free to ask if you’re interested in anything in particular.

Secondary references:

Ceccarelli, Francesco and Marco Folin. Delizie Estensi: Architetture di Villa nel Rinascimento Italiano ed Europeo (Firenze: Olschki, 2009).

‘Dalle Origini al Primo Soggiorno Inglese’ (chapter from unidentified biography of Giovanni Boldini, supplied to the writer).

Entwisle, Peter. ‘Art Beat: Putting Flesh to File on Boldini’, Otago Daily Times, 22 August 2005 p.17.

Entwisle, Peter. ‘Boldini, Louis’ in Southern People: A Dictionary of Otago Southland Biography (Dunedin: Longacre, 1998).

Hitch, John. A History of Braemar House, Woodend, Victoria. 1890-1990 (Woodend: Braemar College, 1992).

Knight, Hardwicke and Niel Wales. Buildings of Victorian Dunedin: An Illustrated Guide to New Zealand’s Victorian City (Dunedin: McIndoe, 1988).

Pepe, Luigi. Copernico e lo Studio di Ferrara: Università, Dottori e Student (Bologna: Clueb, 2003).

Scardino, Lucio and Antionio P. Torresi. Post mortem: Disegni, Decorazioni e Sculture per la Certosa Ottocentesca di Ferrara (Michigan: Liberty House, 1998).

Victorian Heritage Database online.

Acknowledgments:

I would particularly like to thank Jan Warracke, Margaret McKay, and Dominic Romeo in Victoria for their help with images and information.