Built: 1900-1901

Address: West Taieri Cemetery, 1130 Lee Stream-Outram Road

Architects: Mason & Wales

Builders: J.W. Joseph contractor, William Dick stonemason

On the outskirts of Outram is the picturesque West Taieri Cemetery. It sits beside the highway to Middlemarch, as the road begins its ascent of the foothills. Maukaatua presides over the landscape from the southwest. Not far beyond the gates is a striking Gothic mausoleum – an unexpectedly big memorial to come across in a rural Otago burial ground. On closer inspection a plaque is found above the doorway. It tells us this pointy pentagonal pile is the resting place of Daniel Heenan, who died on 9 December 1898, aged 59. I would say final resting place, but… more of that later.

The only grander Dunedin memorials I can think of are the one built for the Larnach family in the Southern Cemetery, and the now mostly demolished one for Bishop Moran in the Southern Cemetery. These were different in conception, being mortuary or memorial chapels with the coffins in vaults beneath them. Daniel Heenan’s remains are above the ground.

Ngaire Ockwell transcribed many of the West Taieri Cemetery headstones in 1979. Daniel’s story had become part of local legend, and Ngaire recorded what she was told:

Daniel was a farmer, and prized the possession of land. He had arranged that on his death, he was not to be buried, but to be laid to rest above ground. This was accomplished by the building of the […] mausoleum, which contains inside it, clearly visible because of the open wrought-iron work of the door, two concrete shelves. On one of these shelves, in a very plain, shallow, wooden coffin, are the human remains of Daniel. I can’t help wondering how long very dry wood can stay in the form of a coffin, while borer busily devour it? The remaining shelf was to accommodate Daniel’s friend. Together, when Christ came to the earth for the second time, Daniel and Friend, as believers in God, would rise up as promised. Logically, as they were not beneath the ground to start with, they would be the first to ‘arise’ and in that instant, they would claim all of the good Taieri land they desired, before the ‘others’ appeared.

Daniel departed this life first, and duly took up his place on a shelf, but his friend’s wife would have none of this nonsense and saw to it that on becoming a widow, her husband was decently buried in the accepted manner. So the second shelf remains vacant and presumably Daniel is free to claim all the Taieri land he desires, without the need to share!

How much of this intriguing tale is true? Ngaire was careful to include a cautionary note stating she had not verified what she was told. Since then, short versions of Daniel’s story have been published from time to time, usually along the lines of the above. What follows is my effort to piece together more than has been told before, and separate some fact from fiction.

Daniel was born in the market town of Birr (then known as Parsonstown) in County Offaly, Ireland, in 1835. He was the fifth of thirteen children of farmers Dennis and Johanna Heenan. Birr had large Catholic and Church of Ireland (Anglican) churches, as well as independent and Wesleyan chapels, and a Quaker meeting house. The Heenans were Catholic until what was known as the Crotty Schism split the local church.

Michael Crotty, the parish’s disaffected curate, began preaching independently in 1826. He found popular support, particularly among the poorer members of the community. For a while his masses attracted higher attendance than the original church. Michael’s cousin William became co-leader, and together the Crottys increasingly adopted a reformed doctrine. From 1836 this included an English mass. The cousins had a volatile off-and-on collaboration and eventually split over divergent allegiances to the Anglican and Presbyterian churches. William took sole charge and adopted the Presbyterian form of worship, with the congregation joining the Presbyterian Synod of Ulster in 1839. Internal division, external hostility, famine, and emigration, all contributed to a sharp decline in membership and the Crotty movement petered out in the 1840s.

The Heenans maintained their Presbyterian affiliation and were still at Birr about 1848. In 1850, Daniel’s parents and ten of his siblings emigrated from Portsmouth, England, on the ship Mariner, arriving in Otago in September. Daniel’s older brother had come out the year before, and another sister would be born in Dunedin.

Settling in North East Valley, the family established a small farm off what is now Norwood Street, Normanby. They cleared bush and built a fern hut thatched with mānuka bark. For food they caught wild pigs, kererū, and weka. Their first crops included potatoes, grown within log fences to protect them from the pigs. While establishing themselves they were helped by mana whenua Māori, who supplied mangā (barracouta) and kūmara.

The Heenans gradually cultivated more land and Dennis took up cattle breeding. The family home was the first dwelling seen when entering the valley from the north, and Susannah offered warm hospitality to passing tramps and other travellers. She was known to sometimes break into spontaneous, exclamatory prayer. Dennis was described as ‘a stalwart man, to whom persevering work was a delight’. In the mid-1850s he took up an additional and larger tract of land in West Taieri, and some of sons would end up managing the family properties. Active Presbyterians, Dennis and Susannah were members of Dunedin’s Knox Church from its establishment in 1860.

In the mid-1850s Daniel followed his two older brothers to the Australian goldfields, working his passage on a small schooner and arriving with only sixpence in his pocket. Over about ten months in Bendigo the brothers made £600 between them. Daniel operated a team of horses in Victoria for three years before returning to Dunedin in the Otago Gold Rush. In 1862 he was briefly in partnership with his eldest brother, Dennis, building and operating the British Hotel in Dunedin. Daniel then ran a successful business carting goods to the Tuapeka and Dunstan diggings, obtaining as much as £100 per ton of freight, but it was difficult work and he lost one of his best horses when ‘snowed up’ on the Lammerlaw Range.

Daniel next turned to farming, taking up freehold and leasehold land in the Maungatua District. The 1882 return of freeholders records him with 331 acres here, while three of his brothers had larger landholdings in the same district. Daniel’s oat threshing machine was put to much use, and in 1892 did all of the threshing for the Hindon District.

Daniel never married. He served on local committees, including the road board. He was associated with the West Taieri Presbyterian Church in the 1870s, and was an enthusiastic proponent of building a new church at Maungatua in 1879. He eventually became disaffected with Presbyterianism. It is tempting to connect this with an 1892 report, which would at least refer to someone Daniel knew:

A rather unusual circumstance occurred at the Maungatua Presbyterian Church. According to a correspondent of the Taieri Advocate one of the congregation interrupted the Rev. Mr Kirkland’s sermon on Justification, Sanctification, and Faith, by standing up with Bible in hand and saying, ‘I can’t listen to ye anither meenit. Ye are just makin’ a perfec’ hash o’ God’s truths. Frae this book (holding up the Bible) I get comfort and counsel ; but from you I can get neither one nor the other’; and after thus delivering himself he walked out of the church. The minister paid no attention to the matter beyond saying, ‘Poor Mr – I am afraid he has misunderstood me.’

What is known is that Daniel left Presbyterian Church and joined the Christadelphians. He was almost certainly among the those who heard the Christadelphian leader Robert Roberts, during his lecture tour in 1896. Roberts preached at Dunedin’s Choral Hall, as well as at Green Island and Mosgiel.

Christadelphians claim to represent the true faith as revived by John Thomas of Brooklyn, New York. Thomas was an English-born restorationist whose movement gained momentum after his 1848-50 tour of the United Kingdom. Christadelphians believe Jesus Christ was a man, not God, and reject the Trinity doctrine as unbiblical. They do not believe in the immortality of the soul and hold that nobody goes to heaven upon death. They say that with the second coming of Christ there will be a resurrection and God’s kingdom will be established on Earth. Christadelphians do not have ordained ministry and local churches are autonomous. Since the start of their movement they have conscientiously objected to war.

The 1896 census records 952 Christadelphians in New Zealand, with 381 in Otago and 32 in the Taieri District. One of the more active groups was at Green Island. In 1898, Gilbert McDiarmid gave a lecture at Hindon on the principles of the Christadelphian movement. McDiarmid was a labourer from a well-known West Taieri farming family, and a newspaper report described him as a fluent and well-informed man who impressed with his earnestness and belief. It was Daniel who introduced the lecture. The Otago Witness reported:

Mr Heenan is evidently an enthusiastic believer in the Christadelphian religion. His rich Irish accent when speaking of the ‘sky hevvins’ was amusing in spite of the solemness of the subject, and many could hardly restrain a smile. Mr McDermid was listened to attentively by his audience, and I venture to assert that if he comes again he will have a larger congregation.

A correspondent to the paper protested that ‘sky hevvins’ was a mishearing, but whatever was said, Daniel’s earnestness cannot be doubted. About this time he became sick, and after an illness of six months he died at a private hospital in High Street, Dunedin, on 9 December 1898, His death registration records his cause of death as heart failure.

Daniel left a convoluted will and a large estate valued at £4,147. To give that figure some context, most school teachers of the time were paid less than £200 per year. The executors were Gilbert McDiarmid and Outram man William Charles Snow. The will was signed in October 1896, and a codicil just three days before Daniel died.

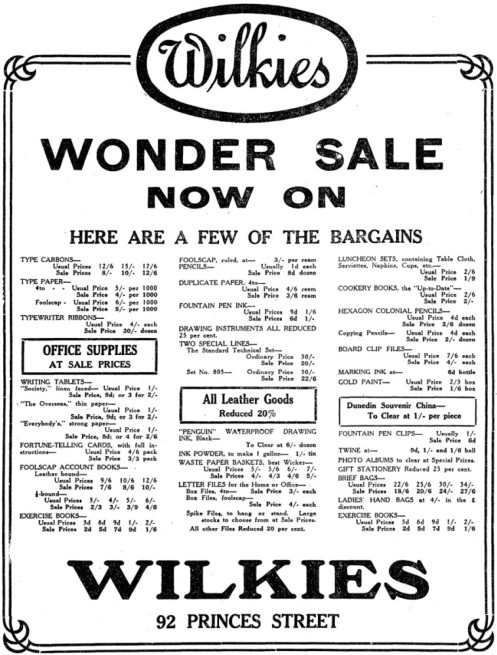

Heenan made monetary bequests to fourteen people, some of them children, totalling £625. McDiarmid received the books and household furniture, and a ‘rich-toned piano’ was sold. £50 was left to Robert Roberts, for the benefit of orphaned Christadelphian children, and £100 was set aside for the erection of a Christadelphian Hall on freehold land. For such a modest sum a small wooden building would have been the most that was affordable. The probate file records that the expenditure was made and a title secured, but I have not found any trace of the building.

Land was left to Daniel’s brother John, to his nephews James Heenan and James Baxter, and to Herbert Scott. Some sections were bequeathed on the condition of a payment to a Christadelphian fund in Birmingham for the relief of destitute Jews, and another on a rental basis, the income to be used to fund annual prizes for local children with Christadelphian parents. The property left to minors went into trust, and if they died before the age of 30 it was to be spent on Christadelphian literature, or to go towards the hall. In return for some land, Baxter was required to pay an annuity towards the relief of destitute Christadelphians ‘of good repute’.

Daniel specified his mausoleum was to be built ‘in some convenient cemetery’. He left £25 for the purchase of plots and £500 for erecting the building. This was more than the average cost of a three-bedroom home. He instructed:

The dimensions shall be 14 feet by 12 feet by 18 feet in height. The walls shall be two feet in thickness of good Portland cement built upon a good rock foundation and with cement benches in the vault to accommodate any of my friends or relations as well as myself. And I direct my Executor to have the following words engraved on a plate fixed on the vault “Go home, my friends, and shed no tears, I must rest here till Christ appears, And when he comes I know that I shall rise, And get from Him the everlasting prize.” “This is my earnest hope”. I direct that my body shall be enclosed in a leaden coffin.

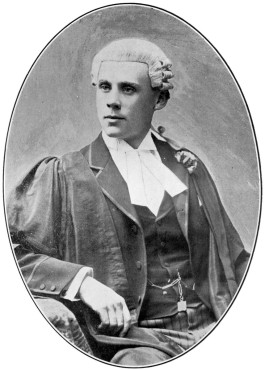

Daniel’s body was temporarily interred on 12 December 1898. Nearly a year passed before, in November 1899, Gilbert McDiarmid approached the architects Mason & Wales. Patrick Young Wales, then the sole director of the firm, sent a sketch for approval in January 1900.

Fortunately, the wonderful archive of Mason & Wales records details of the job. Daniel had not specified whether his remains were to be above or below ground, or at least not in his will. It was Wales who suggested:

Instead of placing the vault underground which would be damp and difficult to ventilate, we propose that the building be wholly above ground, and five sided instead of square, each side measuring 7ft inside. This will give space for twelve or sixteen coffins according to the number of shelves put in, the first being raised a few inches above the floor.

What a lot of coffins! The letter from Wales records more details of the original design:

We propose to set the building on concrete foundations using the Port Chalmers stone you have on the ground for the base course and Oamaru stone for the walls and inside of roof and slated outside. The height of the walls &c 12 ft. The roof will rise 12 ft making the total height above ground 24 ft.

We have shown the door as passed of wood solid and a window on each side. These may be built up solid showing panels instead and the door may be fitted with an iron grill leaving the interior exposed to view which we think would be preferable.

Perhaps we should say why we have made the place five sided instead of square. The size of the ground 15 ft by 14 ft would not, after the thickness of the walls are deducted, have room on any side for two coffins in the length so that with the door on one side, there would only be three sides where coffins could be placed and only one on each side where with the pentagonal form we have four sides with room for one coffin on each side.

Architectural perspective of the mausoleum by Patrick Young Wales, as approved by William Snow for the Cemetery Committee, but later revised.

In February, McDiarmid advised the site had been changed for a smaller one. This necessitated reducing the scale of the building, and no longer allowed for coffins on all sides. Despite the reduction the estimated cost still came in over the £500 allocated. The scale was reduced without altering the design, although Wales suggested the iron door could be plainer, the spire could be timber framed and slated instead of stone, and tracery work could be omitted from the gables. He also raised the possibility of building in concrete, or cement-plastered brick.

A new drawing was ready in May. After tender the contract was awarded to John W. Joseph of Woodside on 7 June 1900, his tender being £420. The specification stated that materials were to be obtained through Mr Snow, and local labour was to be used where possible. It also stated that the plaque should give Heenan’s age as 61, but this was changed to 59, and some sources suggest his actual age was probably closer to 63. Moller & Sons manufactured the plaque.

In early August, Wales made new drawings and working copies, including one for the door. He must have been disappointed and likely annoyed when, on 29 August, McDiarmid wrote to say he no longer required him to supervise the job. McDiarmid said he intended to simplify some things in connection with the plan ‘so as to leave (at least) a payable wage’ to the contractor. In a separate note he wrote:

I am sorry things turned out as they have, I thought you understood that the contract was to be flexible. The body of true believers that I belong to would never think of holding anyone to a contract rigidly that would not pay him. That is the way of the world and the so-called Christian world too but Christendom is Astray in doctrine and practice, but it is not so among us. […] Mr Dick is a magnificent craftsman and is making a beautiful job, I am sure we would all be pleased if you came and had a look unofficially at your design being executed.

That Mr Dick was William Dick of Sandymount can be confirmed by a 1970s reference to a plan of the monument in the Dick family’s possession. William Dick was a master stonemason. Born in 1837, his wealth of experience included much of the work at Larnach Castle, the Portobello Bay Road and other roads, and his own stone farmhouse, ‘Luscar’. Among his monumental work was the headstone for Kāi Tahu rangatira Te Mātenga Taiaroa at Ōtākou.

The newly-completed mausoleum, with stone still on the ground. Otago Witness 15 May 1901. George Hicks photographer. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena.

Presumably Dick acted as subcontractor to John Joseph, who was himself a stonemason and monumental mason, as well as a brick maker. Joseph was also a Christadelphian. The only other mausoleum in the West Taieri Cemetery is one built for John’s wife Elizabeth, who died in 1882. John died in 1907 and was also laid to rest there. There is a note in the burial register that Elizabeth had been interred in another plot. I don’t know when the Joseph mausoleum was erected, but the plot was purchased in June 1883. Gilbert McDiarmid died in 1909 and is buried in the cemetery, but without memorial. Possibly his widow, Janet, was the person described to Ngaire Ockwell as the widow wanting ‘none of this nonsense’.

Daniel’s remains were disinterred and moved to his new mausoleum around the autumn of 1901.

This is about as much as I have found out. If some points are unsettled, it at least seems improbable that Daniel was itching to claim the best farmland on the day of resurrection. There is no record of him directing his coffin to be above ground – it is not in his will, and if his executors had been given additional instructions then the architect would not have needed to make the suggestion. The words Daniel chose refer to receiving ‘the everlasting prize’. It was heaven on earth he was looking forward to.

His monument has captured imaginations over the last 120 years, and is still a place of some mystery. I will leave you with the childhood memory of Madeline Orlowski Anderson. Born in 1907, she described Dan Heenan as a local character who ‘had a gadget built over his grave with a glass front and a suit of clothes in it, there for him to use when he returned. He was coming back. It was a box with a door. I’ve seen it. It was quite a good suit waiting for him.’

Newspaper references:

Otago Daily Times 22 February 1866 p.5 (British Hotel partnership); 26 April 1879 p.20 (proposed new church); 21 July 1890 p,4 (Johanna Heenan obituary); 6 November 1899 p.8 (piano); 16 April 1904 p.5 (William Dick), 17 October 1974 p.14 (William Dick)

Otago Witness 26 April 1879 p.20 (proposed new church); 2 June 1892 p.21 (threshing machine); 25 May 1893 p.3 (interruption of sermon); 9 June 1898 p.30 (McDiarmid’s lecture), 23 June 1898 p.39 (further re lecture); 30 June 1898 p.17 (further re lecture), 15 May 1901 p.34 (photograph of mausoleum); Bruce Herald 24 August 1875 p.5 (call of Rev. Kirkland); Evening Star 24 February 1896 p.2 (Roberts lectures), 21 October 1904 p.6 (Denis Heenan obituary).

Other sources:

Heenan-Davies, Karen. ‘Touching the past: an encounter with some Heenan migrants’, blog post, 9 March 2019, retrieved 7 September 2022 from https://heenan.one-name.net/touching-the-past-an-encounter-with-some-heenan-migrants/.

Holmes, Gwenda. The Berwick Story. Mosgiel: Gwenda Holmes, 2016.

Ockwell, Ngaire. West Taieri Cemetery Otago: Headstone and plans transcript 1859-1979. Dunedin: New Zealand Society of Genealogists, 1979.

Ockwell, Ngaire. West Taieri Cemetery: A transcription of burials, headstones, purchasers and plan, completed in 2009. Dunedin: New Zealand Society of Genealogists, 2009.

Scrivens, Barbara. ‘Madeline Orlowski Anderson’, web article, 2017 (revised 2018), retrieved 7 September 2022 from https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/madeline-orlowski-anderson/.

Death registration for Daniel Heenan. Births, Deaths, and Marriages ref: 1899/250.

Death registration for Gilbert McDiarmid. Births, Deaths, and Marriages ref: 1909/6069.

Death registration for John Williams Joseph. Births, Deaths, and Marriages ref: 1907/4741.

‘Heenan, Daniel’ in Cyclopedia of New Zealand, vol. iv, Otago and Southland Provincial Districts (Christchurch: Cyclopedia Company, 1905) p.648.

‘Mr Denis Heenan’ in Cyclopedia of New Zealand, vol. iv, Otago and Southland Provincial Districts (Christchurch: Cyclopedia Company, 1905) p.385.

‘Daniel Heenan’s Mausoleum’ in Heritage Quarterly, Summer 2013, p.10.

‘Farmers remains lie above ground and without company’. From the Stories in Stone series, Otago Daily Times, 3 September 2005 p.Mag2. (This source was the first to use information in Daniel’s will to explore the story of the mausoleum. It includes research by the late Stewart Harvey).

A return of the freeholders of New Zealand giving the names, addresses, and occupations of owners of land: together with the area and value in counties, and the value in boroughs and town districts, October 1882. Wellington: New Zealand Government Property Tax Department, 1884.

Will and probate file for Daniel Heenan. Archives New Zealand R22045651.

Mason & Wales Architects archive. Correspondence, drawing, and specifications.

Acknowledgments:

Thanks to Mason & Wales Architects for use of their archive. My interest was sparked after finding the mausoleum drawing in their records, and I was delighted to find they had also preserved the specification and relevant correspondence.

My thanks to Ngaire Ockwell for her valuable work, and for permission to quote from it at length.